The Financial Health and Material Hardships of Rural America

Financial insecurity and healthcare shortages weigh heavily on rural communities, a new Financial Health Pulse® analysis finds.

By Wanjira Chege, Andrew Warren, Taylor C. Nelms

-

Program:

-

Category:

-

Tags:

Rural Households Face Greater Financial Struggles and Hardships

From Alaska Native communities to California’s central valley and Appalachian hollers to the Black Belt of the South, rural America is both extraordinarily diverse and characterized by broadly shared economic challenges. Rural communities have long had lower levels of income and higher poverty rates than urban and suburban areas. This is driven partly by shifts in job opportunities from agriculture, mining, and manufacturing toward “knowledge-based” work, which is disproportionately located in cities.1,2,3

Rural poverty is also exacerbated by limited infrastructure. Sparse or unavailable broadband internet, public transportation, financial institutions, hospitals, and other supports all limit low-income rural residents’ access to essential services.4,5,6,7 These gaps go beyond negatively impacting quality of life; in some cases, they can be life-threatening.8 Research has shown that “deaths of despair” – defined as suicide and drug- and alcohol-related deaths – are more common in rural areas and rising faster than in urban areas.9,10

The 2025 Financial Health Pulse® data show that rural households struggle more often with most aspects of financial health than suburban and urban households and are more likely to report experiencing material hardships, such as food insecurity and foregone medical treatment. These disparities are especially concerning as forthcoming cuts to Medicaid leave more people without health insurance coverage and threaten rural hospital revenue, placing added stress on already limited rural health infrastructure.11,12,13

In this spotlight, we use the latest Pulse data to explore some of the financial and physical health challenges disproportionately faced by rural households.

Defining Urbanicity

We categorize households as urban, suburban, or rural depending on their county of residence, using urbanicity categories defined by the National Center for Health Statistics. Following the Pew Research Center’s methodology, we code large central metro counties as urban; large fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro counties as suburban; and micropolitan and noncore counties as rural.

Rural Households Show Lower Financial Health, Savings, and Credit Access

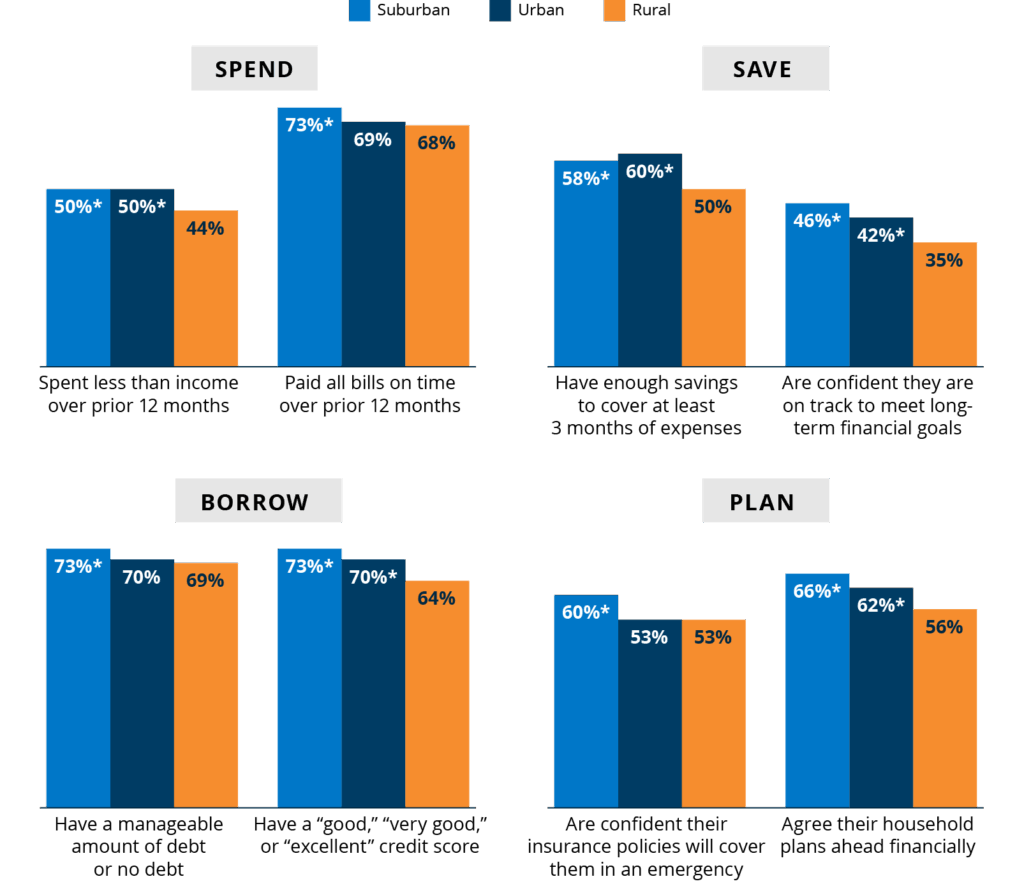

Only 25% of rural households are Financially Healthy, compared with 31% of urban households and 34% of suburban households.14 Rural households fare worse than both urban and suburban households on five of eight financial health indicators: spending relative to income, liquid savings levels, confidence in long-term financial goals, credit scores, and planning ahead financially (Figure 1). While rural and urban households report similar results on the remaining three indicators, rural households fare worse than their suburban counterparts across all eight indicators.

For example, only 50% of rural households report having enough savings to cover at least three months of living expenses, compared with 60% of urban households and 58% of suburban households. This gap is striking considering the lower average cost of living in rural areas, implying that many rural households remain vulnerable to income or expense shocks. Rural households also have lower credit scores than both urban and suburban households, suggesting they struggle to borrow affordably.

Figure 1. Rural households face financial health challenges, especially with saving and access to credit.

Financial health indicators, by urbanicity.

Notes: Data from 2025 Financial Health Pulse survey.

* Statistically significant relative to rural households (at p < 0.05)

Rural and urban households also report lower levels of confidence in their household’s insurance coverage than suburban households. Fifty-three percent of both rural and urban households are at least moderately confident their household’s insurance policies will cover them in an emergency, compared with 60% of suburban households (Figure 1). Part of this gap may be related to differences in health insurance coverage. About 11% of rural households report lacking health insurance, compared with 9% of suburban households and 10% of urban households.

Beyond insurance coverage and quality, a lack of proximity to healthcare services may also contribute to rural households’ lack of confidence in their insurance coverage. Between 2017 and 2024, 62 rural hospitals closed and only 10 opened.15 In August 2025, the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform estimated that 300 additional rural hospitals were at immediate risk of closing.16 Rural households face longer travel times to the hospitals that remain, where fewer services are offered.17

Material Hardships: Linking Financial and Physical Health Challenges

Financial health disparities, coupled with limited access to healthcare and other essential resources, can leave rural households more vulnerable to material hardships. Material hardships are examples of a household’s inability to meet its basic needs, including housing, utilities, food, and healthcare.

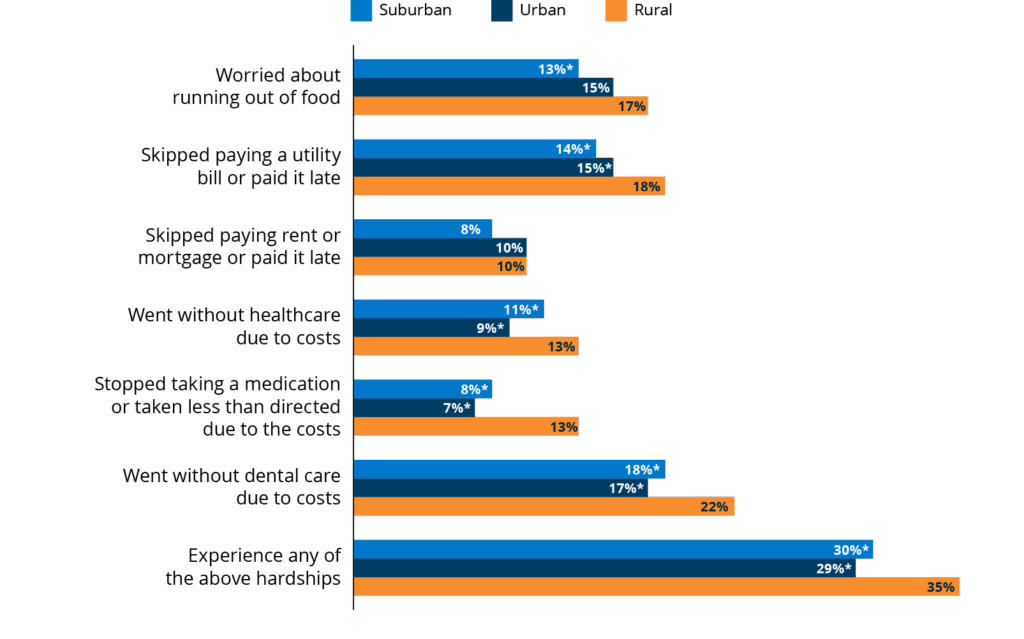

For example, rural households are more likely to report experiencing food insecurity over the past 12 months than suburban households. They are also more likely to skip or delay paying utility bills, forgo healthcare or dental care, and stop taking medication due to costs than both their urban and suburban counterparts (Figure 2).18 Overall, 35% of rural households experienced one or more material hardships in the past year, compared with 30% of suburban and 29% of urban households.

Figure 2. Rural households are more likely to report material hardships than urban or suburban households.

Percentage reporting material hardships in the past 12 months, by urbanicity.

Notes: Data from 2025 Financial Health Pulse survey.

* Statistically significant relative to rural households (at p < 0.05)

Hardships, especially those related to nutrition and skipped healthcare, can lead to worse physical health outcomes. Pulse data show 27% of people in rural areas report fair or poor overall health, compared with 20% of suburban and urban individuals.19 They are also more likely to have a disability themselves or live with someone with a disability (40% vs. 32% vs. 27%).20 Disabilities and health challenges can be expensive to manage, leading to a vicious cycle of health challenges exacerbating financial troubles and vice versa.

Altogether, these findings underscore the compounding impacts of financial strain and limited access to critical health infrastructure in rural communities.21

How Can We Strengthen the Financial Health of Rural Households?

These data points offer a limited snapshot of the complex challenges and opportunities faced by rural communities in America. There is substantial variation between rural communities across the country – by geography, primary industry, race and ethnicity, and age – and these differences shape each household’s unique financial experiences.

On average, however, our data show that rural households are more likely to face financial health challenges and that those challenges translate into higher rates of material hardships. These findings highlight the urgent need to strengthen and protect support for rural households, especially as policy changes threaten access to programs like Medicaid that provide a lifeline to many rural households and health systems.

Financial institutions, employers, and community organizations all play a key role in supporting rural households’ financial health. These recommendations offer a starting point for improving outcomes across rural America.

Expand service delivery in rural banking deserts.22

Financial institutions can invest in mobile-first banking, ATM access points, and shared-service hubs, and support broadband expansion as a foundation for financial inclusion.

Provide tailored products and services for rural households.

Given the significant savings and credit score gaps between rural, urban, and suburban households, prioritizing tools to build liquidity buffers and improve access to affordable credit are two areas for financial institutions to focus on.

Bridge health infrastructure gaps in rural areas.

Employers in rural areas can offer workplace-based benefits, including health insurance, telehealth access, and paid sick leave. Because rural workers often face longer commutes and irregular seasonal employment, employers can provide flexible scheduling and emergency leave to help manage time and mitigate shocks.

Strengthen the social safety net.

As Medicaid and SNAP face cuts and new restrictions, local governments and community organizations will play a vital role in stepping in to shore up the social safety net, provide direct assistance, and help rural residents navigate benefit changes. Policymakers should consider the unique vulnerabilities of rural households when designing eligibility and access rules.

Reduce the financial burden of utilities.

Rural households’ utility payment challenges emphasize the importance of assistance programs such as LIHEAP.23 Rural housing assistance programs that provide weatherization support or incentivize other forms of risk mitigation can reduce monthly utility burdens.

Build nonprofit capacity in rural areas.

Many rural areas lack robust nonprofit ecosystems. Funders can invest in capacity-building so local organizations can deliver and expand financial coaching, benefits navigation, and hardship assistance. Partnerships among hospitals, schools, food banks, and faith-based organizations can strengthen coordination to address financial and health insecurity.

Methodology

Data from this study come from the Financial Health Pulse survey, which is supported by the Principal Foundation. Financial Health Pulse surveys are fielded using the probability-based Understanding America Study online panel at the University of Southern California’s Center for Economic and Social Research, allowing the findings to be generalized to the civilian, noninstitutionalized, adult population of the United States. The 2025 Financial Health Pulse survey was fielded from April 11 through May 19, 2025, with 7,425 respondents and a cooperation rate of 65.69% with a margin of error of +/-1.1%.

About the Financial Health Pulse

Since 2018, the Financial Health Network has conducted the Financial Health Pulse® research initiative. The Financial Health Pulse combines probability-based, longitudinal survey data with administrative data, with the goal of providing regular updates and actionable insights about the financial lives of Americans.

To see more of our Financial Health Pulse research, please visit our Pulse Research page.

- Andrew Dumont, “Changes in the U.S. Economy and Rural-Urban Employment Disparities,” Federal Reserve, January 2024.

- Elizabeth Trovall, “The rural-urban income divide persists, and it may be widening,” Marketplace, November 2023.

- Bradley L. Hardy, Shria Holla, Elizabeth S. Krause, & James P. Ziliak, “Stalled Progress? Five Decades of Black-White and Rural-Urban Income Gaps,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, January 2025.

- “Health Care Capsule: Accessing Health Care in Rural America,” U.S. Government Accountability Office, May 2023.

- Nicol Turner Lee, James Seddon, Brooke Tanner, & Samantha Lai, “Why the federal government needs to step up efforts to close the rural broadband divide,” Brookings Institution, October 2022.

- Carol Kaufmann, “The Digital Divide,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 2024.

- Marci Nielsen, Darrin D’Aostino, & Paula Gregory, “Addressing Rural Health Challenges Head On,” Missouri Medicine, September 2017.

- Gopal K. Singh & Mohammad Siahpush, “Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969-2009,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, February 2014.

- Shannon Monnat, “Deaths Of Despair: Drug, Alcohol, And Suicide Mortality In Small City And Rural America,” Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison, April 2017.

- Jong Hyung Lee et. al, “Urban–Rural Disparities in Deaths of Despair: A County-Level Analysis 2004–2016 in the U.S.,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, October 2022.

- Fredric Blavin, Michael Simpson, & Laura Skopec, “Rural Hospital Revenue Could Drop by $87 Billion over 10 Years Because of the Reconciliation Bill and Expiring Enhanced Tax Credits,” Urban Institute, June 2025.

- Heather Saunders, Alice Burns, & Zachary Levinson, “How Might Federal Medicaid Cuts in the Enacted Reconciliation Package Affect Rural Areas?” KFF, July 2025.

- Michael Shepherd, “What proposed Medicaid cuts could mean for rural communities, hospital access,” School of Public Health, University of Michigan, June 2025.

- Andrew Warren, Shira Hammerslough, Wanjira Chege, & Taylor C. Nelms, “Financial Health Pulse® 2025 U.S. Trends Report,” Financial Health Network, September 2025.

- Scott Hulver, Zachary Levinson, Jamie Godwin, & Tricia Neuman, “10 Things to Know About Rural Hospitals,” KFF, April 2025.

- “Rural Hospitals At Risk of Closing,” Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, August 2025.

- Onyi Lam, Brian Broderick, & Skye Toor, “How far Americans live from the closest hospital differs by community type,” Pew Research Center, December 2018.

- Because rural communities are older on average, we also estimate hardship gaps using logistic regression and controlling for age. The estimated differences shown here persist and even grow slightly after controlling for age.

- Analysis of Financial Health Pulse data, available upon request.

- Analysis of Financial Health Pulse data, available upon request.

- Analysis of Financial Health Pulse data, available upon request.

- Kennan Cepa, Necati Celik, & Wanjira Chege, “Pulse Points Spring 2024: Financial Health Challenges in Banking Deserts,” Financial Health Network, May 2024.

- “Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP),” Office of Community Services, Administration for Children & Families, May 2025.