Understanding the Mental-Financial Health Connection

For the first time, we explore what’s known about the deep relationship between financial and mental health challenges – and what’s left to uncover.

-

Category:

Executive Summary

The American Psychological Association has warned that the United States has reached a “mental health crisis” based on high levels of stress in the country, with vast implications for health and well-being.1, 2 Finances are one of the leading causes of stress.3 Recent Financial Health Network research has found that 4 in 10 Americans (40%) report high or moderate stress from their finances.4 These Americans are disproportionately struggling financially, often facing challenges meeting day-to-day needs.

In recognition of the key role of finances in many people’s lives, a body of research has begun to emerge that aims to better understand the connection between one’s financial and mental well-being. For this brief, the Financial Health Network examined a wide range of literature on stress, financial hardship, and the relationship to mental well-being, with the goal of understanding the current state of knowledge and identifying gaps for future exploration. We couple this with new analysis of our 2023 Financial Health Pulse® data, providing rigorous survey data on stress, financial, and mental well-being from our unique, nationally representative dataset.

Key Findings

1. Americans are stressed, and finances are a top concern. Some populations, such as women, younger individuals, and lower-income households, report elevated levels of financial stress.

2. Financial challenges are associated with mental health challenges. People with the lowest incomes in a given area are 1.5 to 3 times as likely to experience mental health issues, like depression and anxiety, as high-income people in the same area.5

3. However, not everyone responds to financial challenges in the same way. Emerging studies find that some individuals report lower stress levels than others, even in light of similar economic strain. This raises questions about whether there are behaviors or strategies that can help mitigate stress.

4. Researchers have suggested that certain kinds of debt in particular are associated with mental health challenges. Debt that is incurred outside of the individual’s control, such as medical debt, has been associated with mental health issues.

5. Despite the wide body of research available, there is limited evidence of causality – for example, that debt leads to mental health issues. The best evidence to date suggests a bi-directional relationship: Financial challenges may decrease mental well-being, and vice versa. Further research needs to be done to understand the relationship.

The wealth of data establishing a link between mental and financial well-being raises many questions. One worthy avenue for exploration is whether there are coping strategies that can help people manage financial constraints and potentially mitigate mental health impacts. Another, larger implication is whether there are actions we can take as a society to reduce the incidence of the underlying financial challenges – ensuring people have sufficient resources to meet day-to-day needs and manage shocks – and increase availability, affordability, and access to needed mental health care.

Far more work needs to be done to better understand causality, for one, as well as to identify what works best to support individuals who are struggling. Clearly, however, mental health and financial health are closely intertwined. As we consider options for improving the mental health of Americans, supporting financial health should be at the core.

Measuring Mental Health

This brief draws on a range of research on financial and mental well being. Many studies include self-reported aspects of stress and mental health, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, while relatively few rely on clinical definitions of mental illnesses.6 In turn, this brief references both self-assessed and clinical measures. In addition, measures of financial stress and strain vary.

Introduction

The post-COVID period has been marked by widespread economic uncertainty and persistent inflation that strain the finances of many families. Many Americans today are living under severe financial constraints, with 29% reporting that they are unable to pay all their bills on time and 29% reporting unmanageable levels of debt.7 In this volatile time, it is particularly important to understand the impact that such societal and financial uncertainty has on people’s well-being.

As the Financial Health Network works to create a movement that supports financial health for all, understanding the connectivity between financial and mental well-being is critical not only for raising awareness about the issues, but to also point to potential solutions. In this brief, we explore the existing knowledge base around the mental-financial well-being connection and identify potential next steps for research and interventions that could lead to greater, and more equitable, financial health.

This short brief represents our first paper on this topic, and it raises many important questions. The complex interplay between mental and financial well-being has implications for financial institutions, employers, policymakers, and many others. We look forward to future collaboration to better understand how to support people struggling financially – and ensure more people can thrive.

About Financial Health

Financial health, as measured by the Financial Health Network’s FinHealth Score®, provides a holistic way to understand one’s ability to manage their financial lives in the short and long term. Through eight survey questions centered on spending, saving, borrowing, and planning, the FinHealth Score helps categorize respondents into three financial health tiers: Financially Healthy, Financially Coping, and Financially Vulnerable (Figure 1).

Seven in 10 people in America are classified as Financially Coping (struggling with some aspects of their financial lives) or Financially Vulnerable (struggling with almost all aspects of their financial lives).

Figure 1. Interpreting FinHealth Scores.

Stress, Financial Hardship, and Mental Well-Being

For many in America, stress is a way of life. The American Psychological Association’s (APA) 2022 study of stress in America finds that about a third of adults (34%) report that stress is completely overwhelming most days.8 More than a quarter of adults (27%) said that most days they are so stressed they can’t function.9 The 2023 “State of the Global Workplace” poll by Gallup points to a similar story, finding record-high levels of employee stress.10

Finances represent one of the top stressors for many Americans – about two-thirds (66%) of those surveyed for the APA “Stress in America 2022” report said money was a significant source of stress.11 Stress related to money is at the highest level recorded since 2015.12

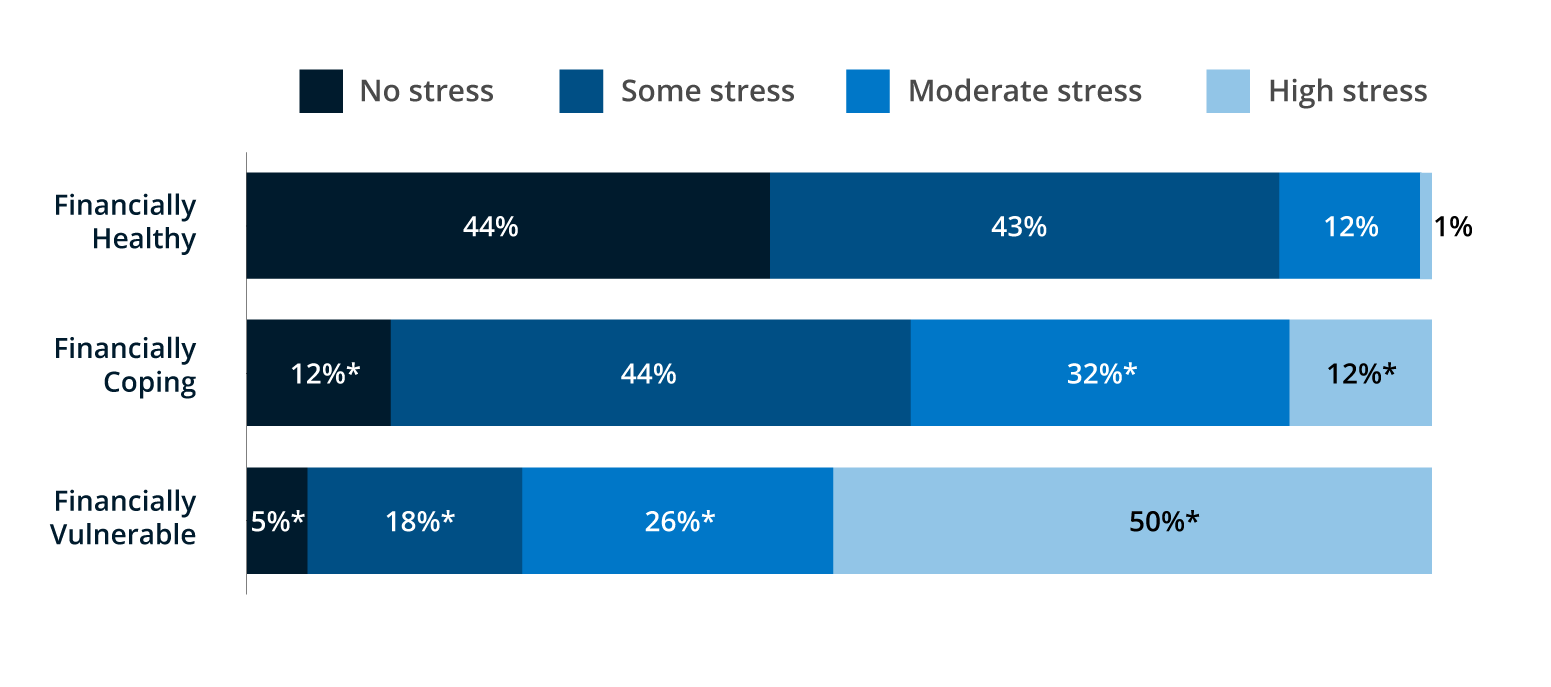

The prevalence of financial stress is perhaps not surprising, given that only about a third of people in America are considered Financially Healthy.13 Our own data from the Financial Health Pulse has consistently found that people who are financially struggling report greater levels of financial stress. In 2023, 76% of Financially Vulnerable people reported experiencing high or moderate stress from their finances, compared with just 13% of Financially Healthy people (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Financially Vulnerable people report dramatically higher levels of financial stress compared with Financially Healthy people.

Level of financial stress, by financial health tier.

Note: * Statistically significant at p < 0.05 vs. Financially Healthy.

Stress Is Not Distributed Evenly

Some populations appear to disproportionately report stress. These groups largely align with those who are more likely to also experience financial hardship, facing larger societal and structural barriers to financial health.14 For example, in addition to lower-income households, women, younger individuals, unmarried people, unemployed people, and renters have been found to disproportionately experience psychological stress of any kind, in particular financial stress.15, 16, 17

Findings by race and ethnicity appear nuanced. One study found that while people of color generally reported more stress than White people, these differences were no longer significant after controlling for other demographic factors.18 Another study on financial anxiety and stress found that, controlling for other demographic variables, Black and Hispanic adults are less likely than their White peers to feel financially anxious.19 Research has yet to establish a consensus on the moderating role of race in experiencing stress.

Limited data is available on people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and agender (LGBTQIA+). Notably, however, the “Stress in America 2022” study found that members of the LGBTQIA+ community were more likely than those who are not to report that, most days, their stress is completely overwhelming (50% versus 33%, respectively).20

Financial Hardship and Mental Health

At the same time, the research is clear: financial hardship is associated with mental health challenges, such as heightened symptoms of anxiety and depression.21, 22, 23, 24 Numerous studies find that participants with low household incomes report greater incidence of psychological distress than those with higher incomes.25, 26 One study found that those with the lowest incomes in a community are 1.5 to 3 times more likely to experience common mental illnesses than the wealthiest within the same community.27 Another found that cash flow challenges (defined as the inability to meet regular bills on time) and deprivation (the inability to provide the essentials of life) were both associated with mental health problems.28

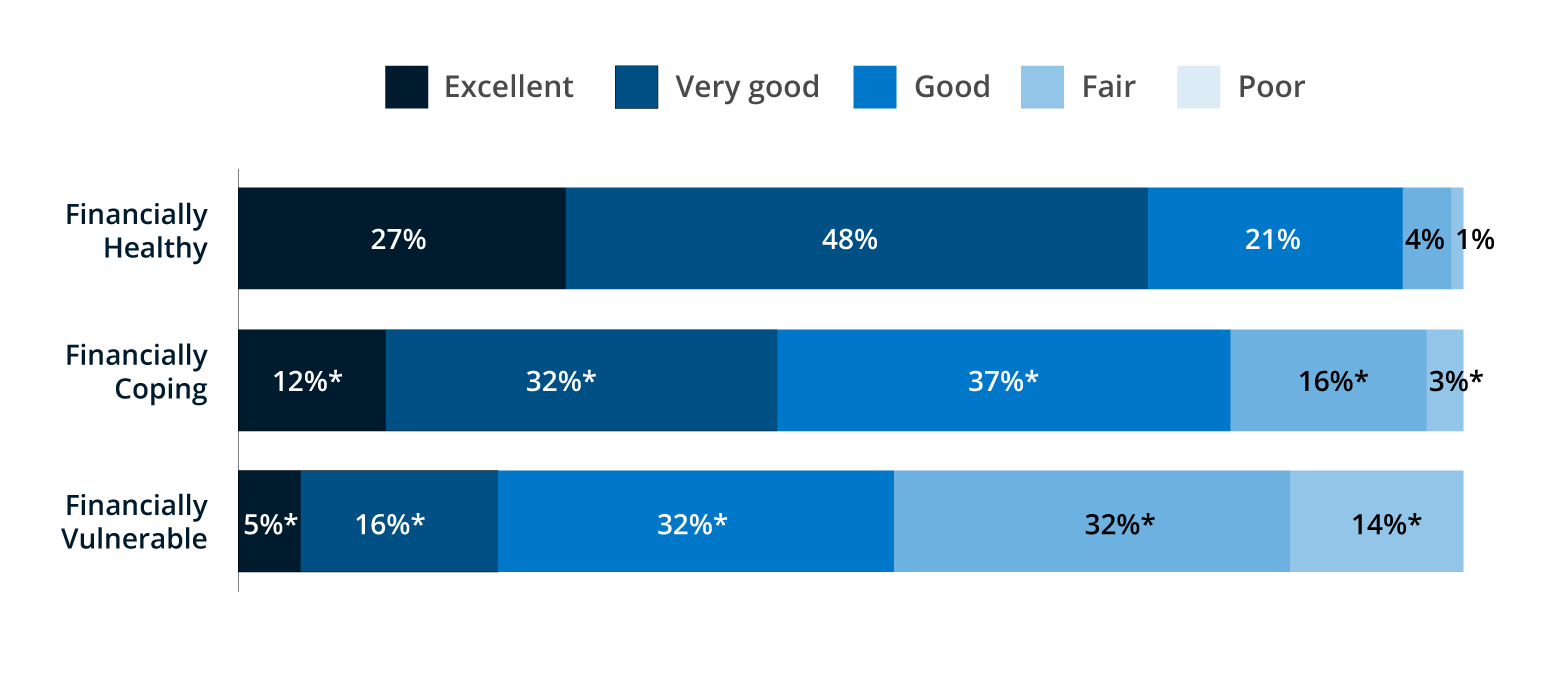

Again, our Financial Health Pulse data corroborate these findings. People who are Financially Coping or Vulnerable report significantly lower levels of mental well-being. Seventy-five percent of Financially Healthy individuals say that their mental well-being is “excellent” or “very good,” compared with 44% of the Financially Coping and just 21% of the Financially Vulnerable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Financially Healthy people say that their mental well-being is “excellent” or “very good” at far higher rates than those who are Financially Coping or Vulnerable.

Self-reported mental well-being, on a scale from poor to excellent, by financial health tier.

Note: * Statistically significant at p < 0.05 vs. Financially Healthy.

Debt Is an Area of Particular Concern

An emerging body of research has honed in on the relationship between debt and mental health.29, 30 A large meta analysis of 65 papers found that the majority of studies identified a relationship between debt and mental health issues, including common mental disorders.31 A paper in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry found that debt burdens have also been associated with increased risk of suicide attempts.32

In particular, personal unsecured debt has been associated with greater depressive symptoms.33, 34 Some researchers have posited that individuals may take on such debt with less agency or choice – for example, accruing credit card debt to cover monthly bills – rather than secured debt like mortgages, which may be seen as an investment.35

29% of Americans reported having “unmanageable” levels of debt in 2023.

Source: Financial Health Pulse 2023 U.S. Trends Report

Medical debt especially stands out as an area of concern.36 Holding medical debt is clearly correlated with lower mental health.37 People with medical debt are three times as likely to have mental health conditions, like anxiety, depression, or stress.38 Further, people holding medical debt report avoiding further medical care, skipping bills, and even delaying college or home ownership at elevated rates.39 Given the wide range of impacts of medical debt on an individual’s health, life quality, and outcomes, many public health researchers consider medical debt to be a social determinant of health – that is, a non-medical condition that shapes an individual’s health, well-being, and quality of life.40, 41

Directionality Isn’t Always Clear

Further research is needed to understand the direction of the relationships – whether, for example, financial health challenges lead to poor mental health, or whether those with poor mental health are more likely to experience financial health challenges.

Some research indicates that, with regard to socioeconomic status and mental health, the relationship is likely bidirectional – that is, the relationship travels both ways.42, 43 Another study found that financial distress is a predictor for depression, and vice versa.44 However, at least one study on debt and depressive symptoms suggests that debt can lead to depressive symptoms, rather than the other way around.45 There is a need for more research, especially longitudinal or repeated cross-sectional studies.46

Creating a Negative Spiral

Research has clearly demonstrated the association between financial hardship and mental health issues, like psychological distress, depression, sleeplessness, and anxiety. Mental health issues, subsequently, are associated with a wide range of additional impacts, including reduced overall well-being, economic activity, and even decision-making.47, 48 These could contribute to a damaging negative spiral of mental, physical, and financial health.

For one, mental health challenges such as depression can affect productivity, impacting one’s ability to concentrate and leading to fatigue.49 Depressed individuals may therefore work fewer days and have lower educational completion, worse early career outcomes, and inhibited skill development.50

Individuals facing financial challenges may not get medical care they need, potentially exacerbating existing health issues. Financial Health Pulse data find that Financially Vulnerable individuals report far lower levels of good physical health than Financially Healthy individuals. In addition, a third (34%) of Financially Vulnerable individuals say they did not receive health care that they needed due to cost, and nearly 3 in 10 skipped or took lower rates of medication than prescribed (Table 1). Similarly, according to a 2019 Kaiser Family Health survey, 5 in 10 individuals facing problems paying medical debt bills report avoiding healthcare services because of their debt.51 In severe cases, debt and financial stress are associated with suicidal ideation, attempt, or completion.52, 53

Table 1. Financially Vulnerable individuals report lower overall health and higher rates of missed medical care than Financially Healthy individuals.

Self-reported health and experience of hardship in the past 12 months, by financial health tier.

| Financially Healthy | Financially Coping | Financially Vulnerable | |

| Had fair or poor overall health | 8% | 18%* | 42%* |

| Forwent needed health care because of cost | 1% | 10%* | 34%* |

| Stopped a medication or took less than directed due to cost | 1% | 7%* | 28%* |

Note: * Statistically significant at p < 0.05 vs. Financially Healthy.

Finally, evidence suggests that people experiencing financial distress may be constrained in their financial decision-making. One study looking at anxiety, financial knowledge, and financial management behaviors found a negative association between anxiety and positive financial management behaviors (holding financial knowledge constant).54 Similarly, in the book “Scarcity,” Eldar Shafir and Sendhil Mullainathan argue that experiencing monetary concerns erodes cognitive performance, resulting in people making choices that are not always in their best interest.55 Still more research has suggested that people experiencing financial stress are less likely to plan for retirement.56

Distinguishing ‘Financial Stress’ from ‘Financial Strain’

An emerging body of research has begun to separate one’s experience of “financial strain” from “financial stress.”57, 58 It’s important to distinguish these two concepts because research has found that it may be possible to experience financial strain without experiencing financial stress, a key factor associated with mental health challenges.

As one example, a 2017 paper found that financially strained respondents who said they were financially stressed reported elevated levels of depression; meanwhile, those who did not report financial stress had depression scores in line with those not experiencing strain.59 Another study of more than 2,000 people in Spain at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic found that, among those who had lost their jobs or experienced income loss, people reporting lower financial stress experienced fewer mental health problems than those reporting greater financial stress.60

What does this mean in layman’s terms? Practically speaking, it suggests that helping people mitigate, or cope with, experiences of financial strain could potentially avoid or lessen mental health issues related to stress. A number of studies have begun exploring the potential factors that may help some individuals mitigate stress, even in light of objective economic challenges. Several have identified psychological and behavioral traits that may help some individuals avoid experiencing financial stress. As one example, individuals with higher levels of perceived “self-efficacy” – the belief that one is competent and can overcome challenges – have been found to demonstrate lower levels of financial stress, even in light of financial strains.61 Similarly, while studies regarding the relationship between financial knowledge and financial stress appear mixed, one’s confidence about their financial knowledge (reporting, for example, that one feels financially educated and well-informed about financial matters) has been associated with lower anxiety.62 Conversely, feelings of hopelessness over finances, a sense that finances will worsen, or a lack of agency – that is, sensing a lack of control – over one’s finances have been associated with mental health issues.63

In recognition of the complex interplay between financial strain and stress, the field of financial therapy has been created, leveraging strategies and approaches from both mental health and financial service professionals in supporting clients.64 Actions like creating a plan for getting out of debt, for example, could be one way for individuals to regain agency and sense of control.65 Other interventions may include restructuring a problem so it is not as overwhelming – for example, breaking a large financial challenge down into smaller behaviors – and helping people to manage their emotions and emotional responses.66

Conclusion

The research is clear: financial and mental well-being are deeply intertwined. This interconnectivity suggests that these topics cannot be approached in isolation and that holistic interventions may be warranted to help clients mitigate experiences of stress. Potential strategies include collaborative activities between mental and financial professionals to help people develop coping techniques and manage their emotions.67

But reducing stress should not be considered a substitute for reducing the very real economic strain that so many in America are experiencing. Far too many people are living on the financial precipice, with low or unpredictable incomes and limited savings cushions. This is coupled with a complex medical and insurance landscape, an acute shortage of mental health providers, and limited coverage even for those who have insurance.68

Many questions remain, and further research is warranted in many areas – among others, to better understand the directionality of the relationship and to explore the experience of specific communities and populations. But above all, the challenge will be to identify what works best in supporting individuals to reduce financial stress, strain, and mental health impacts. In a country in the throes of a mental health crisis, the need is ever more urgent.

Methodology

This brief involved two stages of data review and collection. First, researchers at the Financial Health Network conducted a literature review on the relationship between various aspects of mental and financial well-being. We explored the breadth of research on financial hardship, stress, and financial stress, their prevalence among various communities, and their relationship to mental and physical health. We also examined factors that may either contribute to or mitigate financial stress, and identified areas where further research is warranted.

We complemented this literature review with an analysis of data collected from our 2023 Financial Health Pulse survey, which is part of our initiative to understand how the financial health of Americans is changing over time. The 2023 Financial Health Pulse survey, fielded in April through June 2023 using the Understanding America Study (UAS) online panel, is representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized, adult population of the United States and asks a variety of financial health-related questions. The UAS panel is administered by the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the insights and feedback from many Financial Health Network colleagues, including Matt Bahl, Lisa Berdie, Necati Celik, Kennan Cepa, Wanjira Chege, Angela Fontes, Heidi Johnson, David Silberman, and Andrew Warren.

This report was developed with support from Bread Financial. The insights and opinions expressed in this report are those of the Financial Health Network and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of our partners, funders, and supporters.

![]()

- “Stress in America™ 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis,” American Psychological Association, October 2020.

- “Stress in America 2022: Concerned for the future, beset by inflation,” American Psychological Association, October 2022.

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Analysis of Financial Health Pulse 2023 survey data.

- Matthew Ridley, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, & Vikram Patel, “Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms,” Science, December 2020.

- Frequently, studies use scales to measure self-reported incidence of mental health, including elements such as whether individuals feel stressed, depressed, anxious, or have trouble sleeping. One limitation is that definitions and measures may vary considerably depending on the study cited.

- Kennan Cepa et al., “Financial Health Pulse 2023 U.S. Trends Report: Rising Financial Vulnerability in America,” Financial Health Network, September 2023.

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Ibid.

- “State of the Global Workplace: 2023 Report,” Gallup, 2023.

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Ibid.

- Kennan Cepa et al., “Financial Health Pulse 2023 U.S. Trends Report: Rising Financial Vulnerability in America,” Financial Health Network, September 2023.

- Ibid

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Andrea Hasler, Annamaria Lusardi, & Olivia Valdes, “Financial Anxiety and Stress among U.S. Households: New Evidence from the National Financial Capability Study and Focus Groups,” Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, April 2021.

- Soomin Ryu & Lu Fan, “The Relationship Between Financial Worries and Psychological Distress Among U.S. Adults,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, February 2022.

- Sheldon Cohen & Denise Janicki-Deverts, “Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, April 2012.

- Andrea Hasler, Annamaria Lusardi, & Olivia Valdes, “Financial Anxiety and Stress among U.S. Households: New Evidence from the National Financial Capability Study and Focus Groups,” Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, April 2021.

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Megan R. Ford et al., “Depression and Financial Distress in a Clinical Population: The Value of Interdisciplinary Services and Training,” Contemporary Family Therapy, November 2019.

- Kim M. Kiely, Liana S. Leach, Sarah C. Olesen, & Peter Butterworth, “How financial hardship is associated with the onset of mental health problems over time,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, February 2015.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, Ron Roberts, & Megan Jansen, “A Longitudinal Study of Financial Difficulties and Mental Health in a National Sample of British Undergraduate Students,” Community Mental Health Journal, July 2016.

- Yazan A Al-Ajlouni et al., “High financial hardship and mental health burden among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men,” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, March 2020.

- Soomin Ryu & Lu Fan, “The Relationship Between Financial Worries and Psychological Distress Among U.S. Adults,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, February 2022.

- Jonathan Broekhuizen & R.C. van Geuns, “Should social programs target finances, health, or well-being?,” Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, 2022.

- Matthew Ridley, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, & Vikram Patel, “Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms,” Science, December 2020.

- Kim M. Kiely, Liana S. Leach, Sarah C. Olesen, & Peter Butterworth, “How financial hardship is associated with the onset of mental health problems over time,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, February 2015.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- Lawrence M. Berger, J. Michael Collins, & Laura Cuesta, “Household Debt and Adult Depressive Symptoms in the United States,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, May 2015.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- Diana E. Naranjo, Joseph E. Glass, & Emily C. Williams, “Persons With Debt Burden Are More Likely to Report Suicide Attempt Than Those Without: A National Study of US Adults,” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, April 2021.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- Lawrence M. Berger, J. Michael Collins, & Laura Cuesta, “Household Debt and Adult Depressive Symptoms in the United States,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, May 2015.

- Ibid.

- Lunna Lopes et al., “Health Care Debt In The U.S.: The Broad Consequences Of Medical And Dental Bills,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2022.

- “Medical Debt Burden in the United States,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, February 2022.

- Jacqueline C Wiltshire, Kimberly R Enard, Edlin Garcia Colato, & Barbara Langland Orban, “Problems paying medical bills and mental health symptoms post-Affordable Care Act,” AIMS Public Health, May 2020.

- Lunna Lopes et al., “Health Care Debt In The U.S.: The Broad Consequences Of Medical And Dental Bills,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2022.

- “Social Determinants of Health at CDC,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last updated December 2022.

- “Medical Debt Burden in the United States,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, February 2022.

- Jonathan Broekhuizen & R.C. van Geuns, “Should social programs target finances, health, or well-being?,” Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, 2022.

- Matthew Ridley, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, & Vikram Patel, “Poverty, depression, and anxiety: Causal evidence and mechanisms,” Science, December 2020.

- Megan R. Ford et al., “Depression and Financial Distress in a Clinical Population: The Value of Interdisciplinary Services and Training,” Contemporary Family Therapy, November 2019.

- Lawrence M. Berger, J. Michael Collins, & Laura Cuesta, “Household Debt and Adult Depressive Symptoms in the United States,” Journal of Family and Economic Issues, May 2015.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- Amiram D. Vinokur, Richard H. Price, & Robert D. Caplan, “Hard times and hurtful partners: How financial strain affects depression and relationship satisfaction of unemployed persons and their spouses,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1996.

- “Stress in America,” American Psychological Association, last updated October 2022.

- Jonathan Broekhuizen & R.C. van Geuns, “Should social programs target finances, health, or well-being?,” Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, 2022.

- Ibid.

- “Medical Debt Burden in the United States,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, February 2022.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- “Medical Debt Burden in the United States,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, February 2022.

- John E. Grable et al., “The Moderating Effect of Generalized Anxiety and Financial Knowledge on Financial Management Behavior,” Contemporary Family Therapy, November 2019.

- Sendhil Mullainathan & Eldar Shafir, “Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much,” Center For International Development at Harvard University, 2013.

- Andrea Hasler, Annamaria Lusardi, & Olivia Valdes, “Financial Anxiety and Stress among U.S. Households: New Evidence from the National Financial Capability Study and Focus Groups,” Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, April 2021.

- Sarah D. Asebedo & Melissa J. Wilmarth, “Does How We Feel About Financial Strain Matter for Mental Health?,” Journal of Financial Therapy, 2017.

- Carlota de Miquel et al., “The Mental Health of Employees with Job Loss and Income Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Perceived Financial Stress,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, March 2022.

- Sarah D. Asebedo & Melissa J. Wilmarth, “Does How We Feel About Financial Strain Matter for Mental Health?,” Journal of Financial Therapy, 2017.

- Carlota de Miquel et al., “The Mental Health of Employees with Job Loss and Income Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Perceived Financial Stress,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, March 2022.

- Eva Selenko & Bernard Batinic, “Beyond debt. A moderator analysis of the relationship between perceived financial strain and mental health,” Social Science & Medicine, October 2011.

- John E. Grable et al., “The Moderating Effect of Generalized Anxiety and Financial Knowledge on Financial Management Behavior,” Contemporary Family Therapy, November 2019.

- Thomas Richardson, Peter Elliott, & Ronald Roberts, “The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Clinical Psychology Review, December 2013.

- “Financial Therapy Association – Money, Mind-Body, Research and Relationships,” Financial Therapy Association.

- Sarah D. Asebedo & Melissa J. Wilmarth, “Does How We Feel About Financial Strain Matter for Mental Health?,” Journal of Financial Therapy, 2017.

- Richard S. Lazarus & Susan Folkman, “Stress, Appraisal, and Coping,” Springer Publishing Company, March 1984.

- Sarah D. Asebedo & Melissa J. Wilmarth, “Does How We Feel About Financial Strain Matter for Mental Health?,” Journal of Financial Therapy, 2017.

- Stephanie Brooks Holliday, Kimberly A. Hepner, & Harold Alan Pincus, “Addressing the Shortage of Behavioral Health Clinicians: Lessons from the Military Health System,” RAND Corporation, May 2022.