Responding to Reform: Overdraft in 2023

After pivotal reforms in 2022, this FinHealth Spend Product Spotlight sheds light on the state of overdraft fees today, how consumers use overdraft, and potential implications for financial institutions and policymakers.

By Meghan Greene, MK Falgout, David Silberman

-

Program:

-

Category:

-

Tags:

Introduction

Last year, the Financial Health Network’s brief Overdraft Trends Amid Historic Policy Shifts offered overdraft and non-sufficient funds (NSF) fee estimates and survey analyses for the 2022 calendar year – a pivotal year of change in overdraft policies nationwide.1, 2

This brief offers an update with new data for 2023. Given that many of the largest bank policy changes were made in 2022, this piece examines consumer trends and behaviors after this period of upheaval, providing important insight into the scope and volume of the regulatory changes. As the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) considers a rulemaking that would likely further curtail overdraft fees among institutions with $10 billion or more in assets, our most recent data can help guide decision-making in support of greater financial health.3

In this brief, we draw from secondary analyses to estimate total overdraft/NSF fees for all financial institutions (including smaller banks and credit unions). We pair these data with a nationally representative survey conducted in January 2024, which asked respondents about financial product usage during 2023. This brief is a companion piece to the FinHealth Spend Report 2024. For further details, see Methodology.

What Is Financial Health?

Financial health is a composite measurement of a person’s financial life. Unlike narrow metrics such as credit scores, financial health assesses whether people are spending, saving, borrowing, and planning in ways that will enable them to be resilient and pursue opportunities. The analysis we present in this brief leverages the FinHealth Score® framework, which is based on eight survey questions that align with the indicators of financial health.

Approximately two-thirds of people in America are classified as Financially Coping (struggling with some aspects of their financial lives) or Financially Vulnerable (struggling with almost all aspects of their financial lives).

Survey Respondents Report Few Differences Compared With 2022

As reported in the FinHealth Spend Report 2024, total overdraft/NSF fees in 2023 are estimated to be $7.9 billion, a 19% decline from 2022’s estimate of $9.8 billion – and nearly 50% lower than 2019’s figure ($15.5 billion).4 Despite this continued contraction, however, survey data show remarkable stability in the reported incidence of overdraft. Among households with checking accounts, 17% reported paying an overdraft or NSF fee in 2023, the same as 2022.5, 6

Similarly, the number of reported overdrafts broadly stayed the same between 2022 and 2023, with Financially Vulnerable households far more likely to report high volumes of overdrafts.7 Overall, 9% of overdrafting households reported more than 10 overdrafts in 2023, unchanged from 2022.8

We also continue to find that while many overdrafts are due to an accidental overdraw, a minority of households intentionally overdraw their accounts, knowing they would incur a fee. When thinking about their last overdraft, 51% of respondents said, “I did not realize my account balance would not cover the expense,” statistically the same as last year. About a quarter (26%) took a gamble – saying that they knew their account balance was low, but thought there was a chance it would cover the expense – while 18% said they knew their account balance wouldn’t cover it. These findings, too, are in line with last year’s figures, as is the fact that frequent overdrafters (those who overdraft 10 or more times), low-income households, and Financially Vulnerable households are more likely to report that they were at least somewhat aware of a risk.

The reported transaction size that triggered the fee stayed flat, with about a quarter of respondents (24%) saying their last overdraft was on a purchase or payment of $25 or less. This is despite the increase in the size of fee cushions among numerous banks.9 Forty-five percent (45%) reported their last purchase that incurred an overdraft was $50 or less, unchanged from 2022.

Another key finding on consumer preference for overdraft remained unchanged from 2022. Sixty percent (60%) of overdrafters said that when they overdrafted most recently, they would have preferred to incur the fee and ensure the payment be processed. This preference is more common among those who overdraft more frequently.

Without Overdraft, Many Would Not Have Made the Purchase

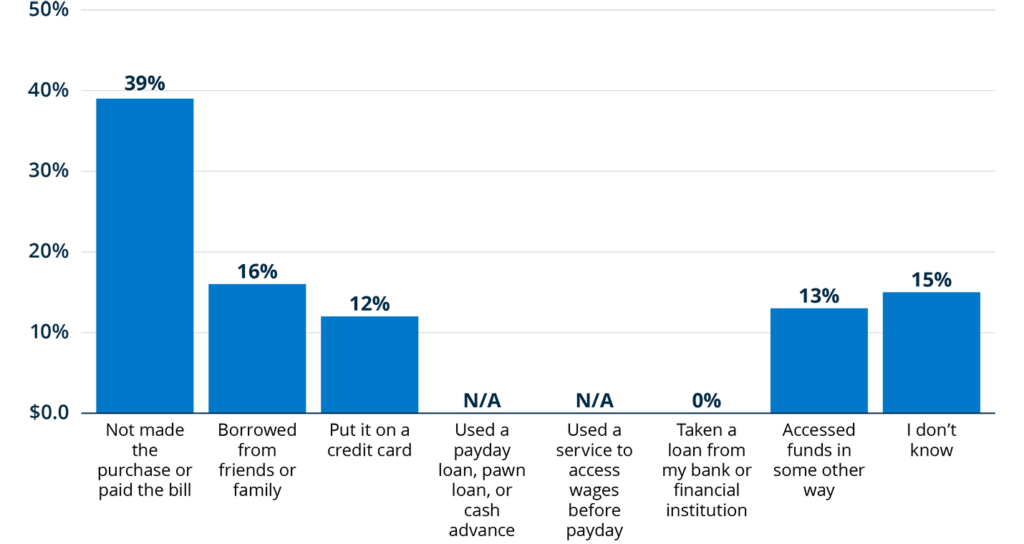

The issue of a “counterfactual” – what people would do if overdraft were not available – has been a central issue of discussion in the overdraft debate. Voices arguing in favor of overdraft protection claim that, if overdraft were not available, people would turn to high-cost payday or pawn loans.10 Meanwhile, a number of large banks have begun offering rapid, small-dollar loans and lines of credit as possible lower-cost alternatives, and numerous companies have introduced technologies that advance access to earned wages.11, 12

To shed light on this issue, we added a question to the 2023 survey that asked a subset of overdrafters what they would have done during their most recent overdraft transaction if overdraft were not available. We specifically asked this question among only those who overdrafted intentionally, as this group consciously made a choice to overdraft the account (and incur the fee) to ensure a purchase or payment went through. The group that overdrafts intentionally is almost exclusively Financially Coping or Vulnerable.

While sample sizes are small (n=114), very few people said they would have either used a service to access wages before payday or utilized an alternative credit product like a payday, pawn, or cash advance loan. Furthermore, not a single respondent answered that they would have “taken a loan from my bank or financial institution,” which could suggest a lack of awareness about the availability of relatively new, lower-cost loans.13 Rather, a plurality of respondents (39%) said they wouldn’t have made the purchase or paid the bill. For at least some of these individuals – who made the intentional decision to incur an overdraft fee to finance a purchase – this finding suggests a pressing need for immediate liquidity, without which they would not be able to make the purchase.

Figure 1. Nearly 4 in 10 intentional overdrafters said they would not have made the purchase or paid the bill.

Alternative payment source, among intentional overdrafters.

(n=114)

Notes: Responses to “Thinking about your most recent overdraft experience, if overdraft were not available, I would have…” Response options were “Taken a loan from my bank or financial institution;” “Used a service such as a payday loan, pawn loan, or a cash advance;” “Used a service to access wages before my payday;” “Borrowed from friends or family;” “Put it on a credit card;” “Accessed funds in some other way;” “Not made the purchase or paid the bill;” and “I don’t know.” No respondents selected “Taken a loan from my bank or financial institution” as an option, and too few responded “Used a service such as a payday loan, pawn loan, or a cash advance” or “Used a service to access wages before my payday” to report.

New Data on Overdraft by Race Reveal Disparities

Previous FinHealth Spend data has established that banked households of color are more likely to incur at least one overdraft/NSF fee than white households.14 This disparity remains true in 2023: 31% of Black households and 24% of Latinx households with checking accounts reported being charged an overdraft fee in 2023, compared with 14% of white households. That said, as in prior reports, we do not find evidence that overdrafting households of color are more likely to overdraft frequently (10+ times) than overdrafting white households.15, 16

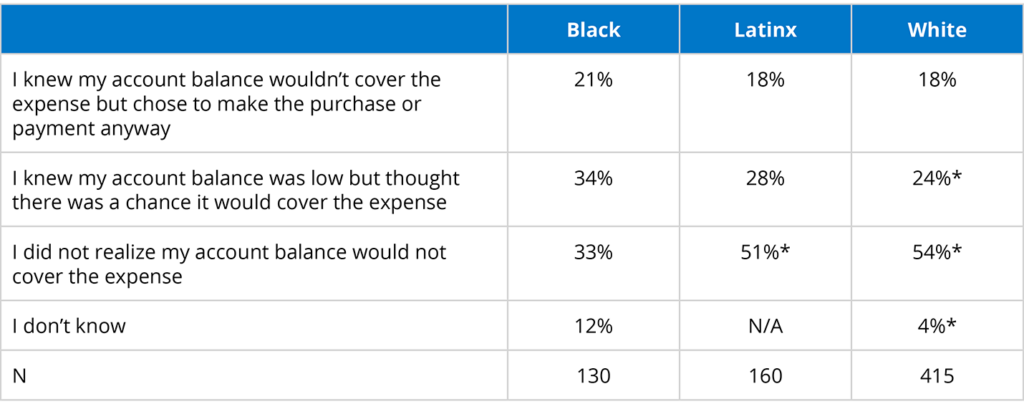

However, this year, we start to shed additional light on the disproportionate impact of overdraft among Black communities. First, when thinking about their most recent overdraft, Black households reported that they were aware that the purchase or payment might result in an overdraft at greater rates than white households, who more often reported that the overdraft was unintentional. More than half (55%) of Black overdrafters said that they were aware that there was at least some risk, compared with 42% of white overdrafters.17

Table 1. Over half of Black households that overdraft report knowing there was at least some risk of incurring a fee.

Intentionality of overdraft, by race/ethnicity.

Notes: Responses to the question, “Thinking about your most recent overdraft/NSF experience, which of the following is most accurate?” Too few Latinx respondents reported “I don’t know” to report.

* Statistically significant difference compared to Black respondents (p < 0.05).

Furthermore, our 2023 data finds a small but statistically significant difference in the size of the purchase or payment that incurs an overdraft. Thirty-one percent (31%) of Black overdrafters said their most recent overdraft was on a purchase or payment of $25 or less, versus 22% of white overdrafters. Conversely, only 22% of Black overdrafters said their last overdraft was on a purchase or payment of $100 or more, compared with 33% of white households.

Taken together, these data points suggest that Black households are more frequently faced with circumstances that lead them to incur or risk incurring an overdraft fee. Intentional overdrafts are more frequently made by those in difficult financial circumstances, and with the average overdraft fee still at about $30-$35, incurring those costs for a $25 purchase suggests a lack of other attractive and immediate options.

Implications for Future Overdraft Policy

Proponents of overdraft protection argue that overdraft services provide an important source of liquidity and that customers want overdrafts. On their face, both statements are true: Many households report few alternatives to overdraft, and a consistent majority report a preference for incurring the fee versus having the purchase declined.

Yet, we also consistently find that it is Financially Vulnerable individuals who are paying the most in overdraft fees and that these fees are often applied to relatively small-dollar purchases. Our 2023 data continue to suggest that overdraft fees, in the aggregate, are disproportionately borne by those who are least able to absorb them.18 We estimate that the average Financially Vulnerable household – a group characterized by scarce savings cushions and expenses that consistently exceed income – paid over $200 in overdraft fees in 2023. Further, other research suggests that many households believe the standard fee is unreasonable. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center study, 7 in 10 Americans (71%) believe that it is unfair for a bank to charge a $35 overdraft fee.19

These findings, together, suggest that while overdraft protection can serve as an important source of liquidity, the costs can be burdensome. The challenge, then, lies in crafting overdraft policies in such a way that they do not limit access to needed credit while still providing for fair and reasonable fees that allow institutions to cover their costs. Our data also suggests a continued need for development – and perhaps promotion of – overdraft alternatives that provide liquidity at lower costs, as well as strategies that improve financial stability and security writ large.

Methodology

Data for this release come from both primary and secondary data sources.

All survey data are drawn from the 2024 FinHealth Spend survey, with data collected between January 3-Feb 3, 2024, using the Understanding America Panel. Understanding America is a probability-based panel of consumers age 18+ designed to be representative of the U.S. population. The study included responses from 5,509 consumers from unique households (margin of error +/- 1.3pp).

National estimates of overdraft/NSF fee totals come from a model developed using data from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) Central Data Repository (2019-2023); National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) Aggregate Financial Performance Reports (FPRs) (2020-2023); and “Data Point: Overdraft/NSF Fee Reliance Since 2015 – Evidence from Bank Call Reports,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2021).

About the FinHealth Spend Report

The FinHealth Spend Report, previously known as the Financially Underserved Market Size Study, is one of the Financial Health Network’s longest-running research initiatives. The report analyzes household spending on dozens of financial products and services, leveraging extensive secondary research as well as a nationally representative survey on consumer spending. Through this initiative, we gain insight into the impact that interest and fees have on families in the United States and uncover disparities in our system.

We are grateful for the support and guidance of numerous Financial Health Network colleagues, including Hannah Gdalman, Lisa Berdie, Angela Fontes, and Necati Celik.

The FinHealth Spend Report is made possible through the financial support of Prudential Financial.

- Allissa Kline, “How 2022 hastened the decline of overdraft fees,” American Banker, December 2022.

- For simplicity, in most instances in this brief we refer to overdraft and NSF fees as “overdraft fees,” intending the term to apply to both sources. However, policy reforms for NSF and overdraft differ, with many banks having eliminated NSF fees outright over the past few years. The CFPB has also found that most NSF fee payers incur overdraft fees. See: “Overdraft/NSF metrics for Top 20 banks based on overdraft/NSF revenue reported during 2021,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, April 2024, “Non-sufficient fund (NSF) fee practices of the 25 banks reporting the most overdraft/NSF revenue in 2021,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, May 2023, and “Overdraft and Nonsufficient Fund Fees: Insights from the Making Ends Meet Survey and Consumer Credit Panel,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, December 2023.

- “CFPB Proposed Rule to Close Bank Overdraft Loophole that Costs Americans Billions Each Year in Junk Fees”, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, January 2024.

- Hannah Gdalman, MK Falgout, Necati Celik, Ph.D., & Meghan Greene, “FinHealth Spend Report 2024,” Financial Health Network, August 2024.

- In 2022 and 2021, 17% of households with a checking account reported paying an overdraft fee. In 2020, the first year our survey was deployed, the incidence rate was 16%, not a statistically significant difference.

- Similarly, the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking found no significant change in the incidence of overdraft between 2022 and 2023, though their figure is slightly different at 12% for 2023 and 11% for 2022. See: “Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 2024.

- We do not find any statistically significant shifts in the percentage of overdrafters who responded that they had paid “3-5”, “6-10,” or “More than 10” overdrafts in 2023, as compared to 2022. We do, however, find a statistically significant increase in the share of respondents reporting they paid two fees, as opposed to one fee.

- The CFPB has found that 14% of overdrafting households had more than 10 overdrafts in the prior year. See: “Overdraft and Nonsufficient Fund Fees: Insights from the Making Ends Meet Survey and Consumer Credit Panel,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, December 2023.

- “Overdraft/NSF metrics for Top 20 banks based on overdraft/NSF revenue reported during 2021,” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, April 2024.

- “The Value of Overdraft Services,” Consumer Bankers Association.

- Alex Horowitz & Gabriel Kravitz, “Six of the Eight Largest Banks Now Offer Affordable Small Loans,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, February 2023.

- Lisa Berdie & Riya Patil, “Exploring Earned Wage Access as a Liquidity Solution,” Financial Health Network, November 2023.

- Alex Horowitz & Gabriel Kravitz, “Six of the Eight Largest Banks Now Offer Affordable Small Loans,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, February 2023.

- MK Falgout, Meghan Greene, & Necati Celik, “Overdraft Trends Amid Historic Policy Shifts,” Financial Health Network, June 2023.

- Ibid.

- The Federal Reserve Board’s Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in the 2023 report similarly found no change in the overall incidence of overdraft, though at different levels. See: “Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May 2024.

- In 2022, 20% of Black overdrafters said they overdrew their account intentionally, 23% said they knew there was a risk, and 47% said they did not realize they would incur a fee. The latter two are both statistically different from 2023.

- We estimate that Financially Vulnerable households comprise 15% of the population overall but account for 47% of total overdraft fees, with an average of $201 in fees per household (banking status is not taken into account in this equation).

- Alex Horowitz, Linlin Liang, & Gabe Kravitz, “Americans Support Affordable Small Loans in the Banking System,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, June 2023.