Pulse Points Summer 2023: Weathering Financial Setbacks From Natural Disasters

Severe weather can disrupt financial health, yet fewer than expected Americans living in disaster-prone areas carry residential insurance.

By Kennan Cepa, Ph.D., Wanjira Chege, Angela Fontes, Ph.D.

-

Program:

-

Category:

-

Tags:

Introduction

In 2022 alone, Americans experienced 90 natural disasters, 18 of which sustained losses of $1 billion or more.1, 2 Those figures aren’t an anomaly: As climate change increases the frequency and severity of extreme weather events and populations increasingly settle in affected areas, Americans will face greater risks.3, 4

In particular, natural disasters lead to injury and loss of life, property, and belongings. This can result in unexpected employment disruptions or loss of income, as well as expenses for temporary housing and repairing or replacing property or belongings.5, 6 These unexpected, natural disaster-related expenses can have concerning ramifications for financial health.

Insurance policies, such as homeowners or renters insurance, can cushion households against some of these shocks to safeguard financial health.7 For instance, homeowners insurance can help manage the cost of repairing or replacing a home and the belongings inside it. In cases where homeowners are temporarily unhoused because of damage to their home, homeowners insurance can also cover the costs of alternative housing.8 Renters insurance is designed to help cover the cost to replace or repair any belongings in a rental property damaged in a natural disaster, and some policies will also cover the cost of finding alternative housing.9, 10 Thus, residential insurance, whether through homeowners or renters policies, can help consumers maintain financial health in the wake of a disaster.

However, not all consumers carry residential insurance. Some consumers prefer not to purchase insurance, especially if they are unaware of their risks or perceive their risks to be manageable.11 The cost of insurance products can also act as a barrier, with low-income households less frequently covered by insurance than high-income households.12, 13, 14 In addition, recent shifts in the insurance market indicate that it may become more difficult to purchase insurance, especially in states severely impacted by natural disasters. As property losses incurred from natural disasters increase, some insurance companies are raising prices or declining to extend new personal line policies, which includes homeowners and renters insurance, in certain states.15, 16, 17, 18 Because insurance markets are regulated at the state level, these policy changes can leave Americans throughout an affected state with limited options to protect themselves from a disaster.

Since insurance offers financial protection in the wake of a natural disaster, we would expect greater uptake of residential insurance among Americans living in states that experience high losses related to natural disasters. Instead, this Pulse Points brief finds the opposite.

Using 2021 Financial Health Pulse survey data combined with state-level FEMA records of natural disaster-related losses experienced through 2021, we categorize states as either high-loss or low-loss based on their expected annual losses associated with natural disasters. A state’s expected annual losses are calculated by FEMA as the sum of the average building, population, and agriculture value lost from 18 types of natural disasters.19

High-Loss States

The average loss per state is $632,452,992, which is the sum of the expected annualized loss from avalanches, coastal flooding, cold waves, droughts, earthquakes, hail, heat waves, hurricanes, ice storms, landslides, lightning, riverine flooding, strong winds, tornadoes, tsunamis, volcanic activity, wildfire, and winter weather.

States with higher-than-average annual losses include California, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Missouri, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington.

Our brief draws on this data to document a gap in insurance coverage between those living in high- and low-loss states. Based on our findings, we offer recommendations for insurance providers, financial institutions, state and local governments, and landlords to help Americans weather the financial fallout of natural disasters.

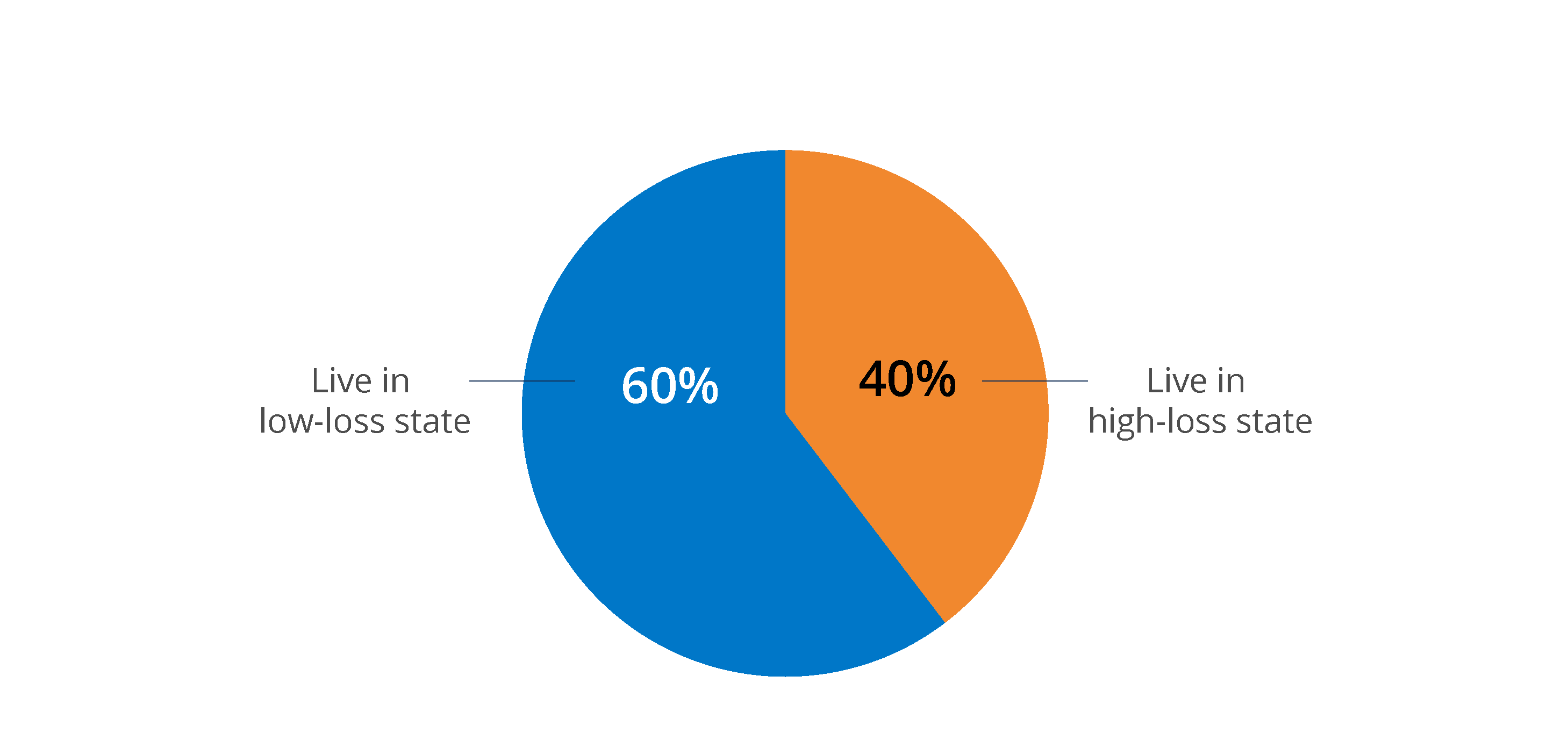

2 in 5 Americans Live in 11 States at Higher Risk for Natural Disaster Losses

Our research shows that two out of five (40%) Americans – 103.4 million in total – live in 11 high-loss states with above-average expected annual losses from natural disasters.20

This suggests that the potential to experience loss from a natural disaster is widespread, emphasizing the importance of purchasing adequate homeowners or renters insurance to prepare for such a possibility. It also indicates that the coverage of a considerable share of Americans may be impacted in the future as insurers raise rates or decline to issue new policies in certain states.

Figure 1. 2 in 5 Americans could experience higher-than-average natural disaster losses.

Percentage of people living in high-loss versus low-loss states.

Note: Loss from natural disaster occurrence determined with FEMA data. N = 5,648 respondents.

Losses from natural disasters are also an equity issue. Those living in high-loss states were more frequently Financially Vulnerable than residents of low-loss states and were also disproportionately Asian, Latinx, or selected multiple races or ethnicities (analyses not shown).21 These findings point to the increased importance of insurance to safeguard the finances of those living in high-loss states, since they may find it especially challenging to weather the financial consequences of a natural disaster.

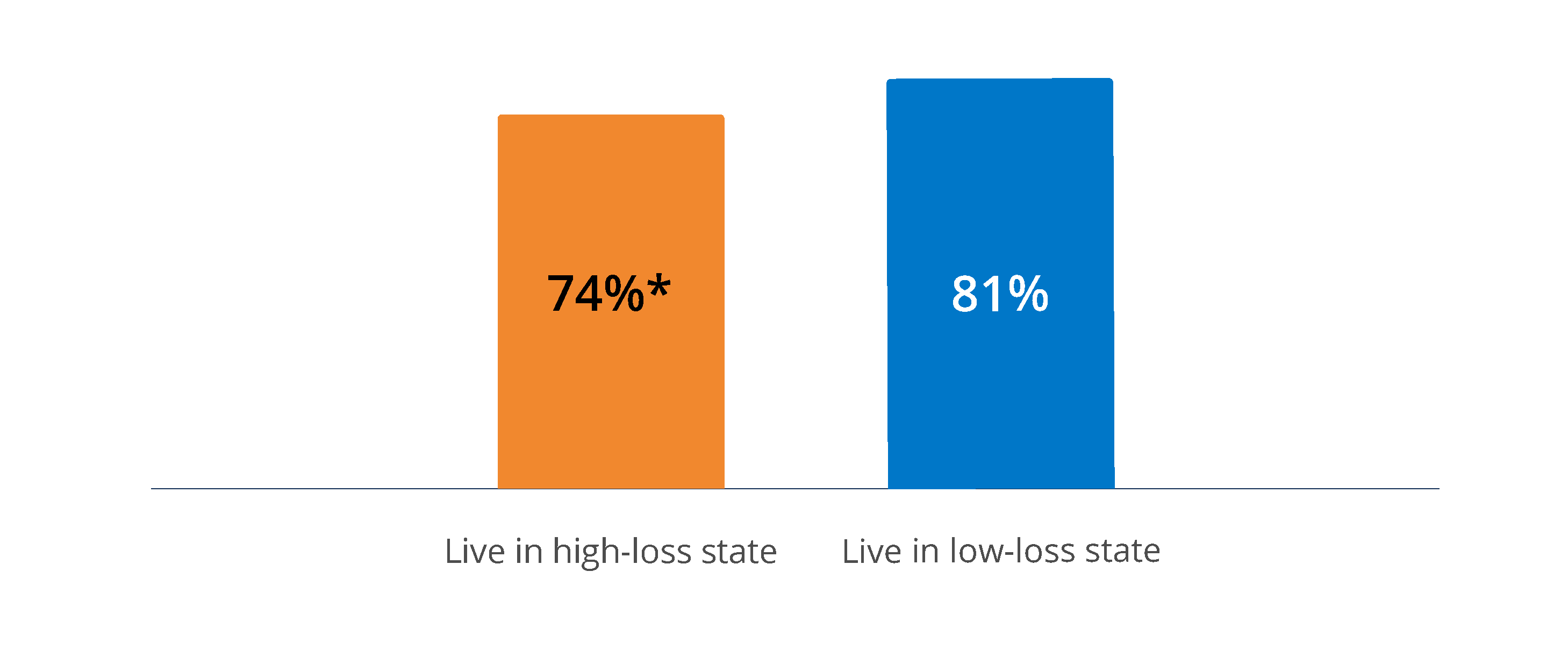

Residents of High-Loss States Less Frequently Use Residential Insurance

Insurance can play a critical role in managing the financial challenges that arise in the aftermath of a disaster.22 Yet, we find that renters and homeowners living in high-loss states were less frequently covered by residential insurance than those living in low-loss states (Figure 2). With lower rates of insurance coverage among residents of states facing the greatest losses from natural disasters, consumers in high-loss states may be financially unprepared should a disaster occur. Moreover, given that residents of high-loss states were more often Financially Vulnerable, they may not have the financial resources to cover unexpected expenses in the wake of a disaster.

Figure 2. Residents of high-loss states carry residential insurance less frequently.

The percentage of homeowners and renters covered by residential insurance living in high-loss versus low-loss states.

Note: * Statistically significant vs. people living in low-loss states (p < 0.05). N = 5,648 respondents.

Indeed, in the wake of a disaster, prior research finds that disparities often widen.23 Although this brief does not examine what happens to consumers’ financial health in the aftermath of a disaster, access to residential insurance in high-loss states may be a contributing factor to financial health disparities. For instance, in analyses not shown, we find that residential insurance coverage is lower among Asian, Black, and Latinx residents of high-loss states relative to White residents of those same states. Assuming that residential insurance offers adequate protection to consumers, this suggests that people of color are less likely to be shielded from financial losses incurred by a natural disaster and may contribute to disparities in wealth among residents of high-loss states.

Lower Residential Insurance Coverage in High-Loss States Driven by Disproportionate Share of Renters

In part, the low rates of residential insurance coverage in high-loss states are driven by the disproportionate share of renters in these states. Over a third (37%) of residents in high-loss states rented their homes, but renters comprised only 27% of residents in low-loss states (Figure 3). Consistent with other research, we also find that renters purchased renters insurance at relatively low rates, regardless of the natural disaster loss in their state (analysis not shown).24, 25, 26

In the event of a disaster, renters are not responsible for financing repairs to the building where they live, but they may need to replace or repair belongings that are damaged or destroyed. Navigating the financial implications of a disaster without insurance may be especially challenging for renters because they typically have lower incomes, less wealth, and lower financial health than homeowners.27 In addition, renters are more often Black or Latinx, so experiencing a natural disaster without insurance may contribute to racial disparities in financial health.28

Figure 3. Residents of high-loss states are more frequently renters.

Percentage of residents who are renters by residence in high-loss and low-loss states.

Note: * Statistically significant vs. people living in low-loss states (p < 0.05). N = 5,648 respondents.

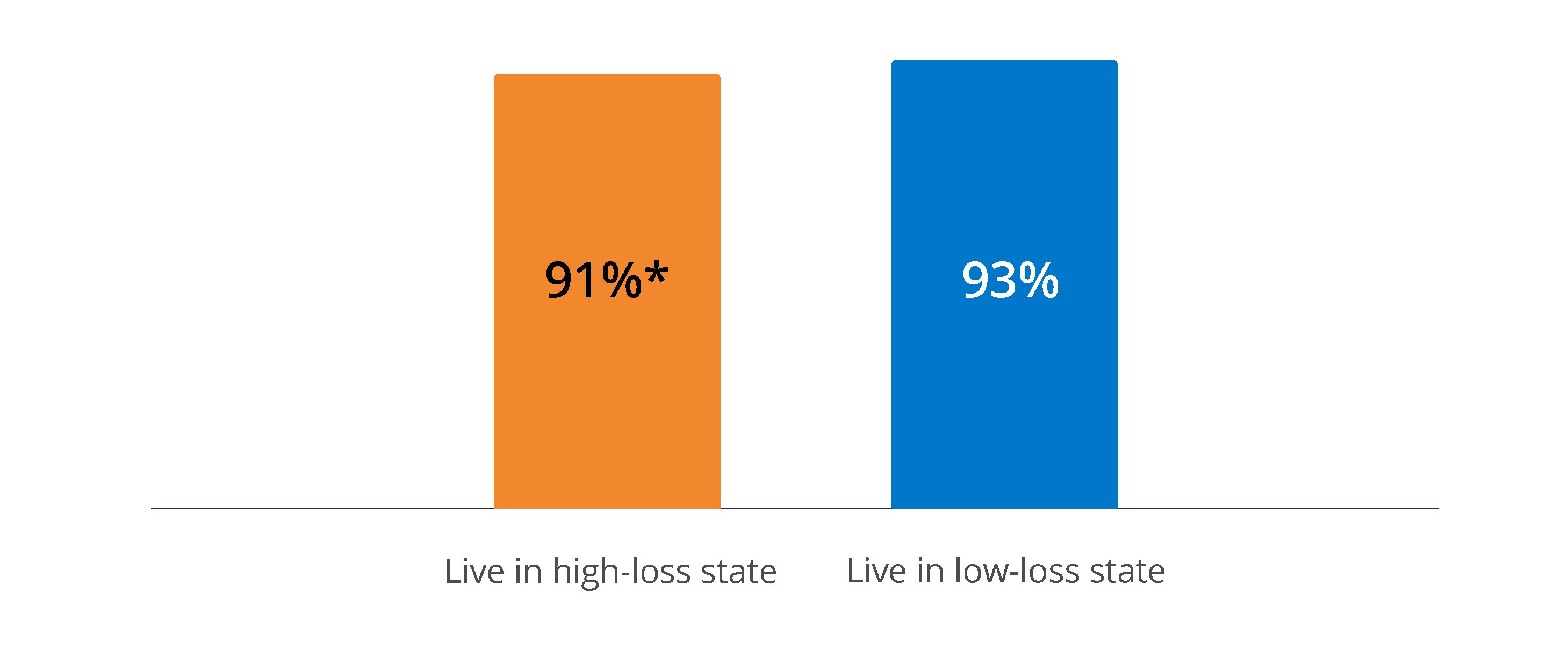

Homeowners Less Frequently Carry Insurance in High-Loss States Than in Low-Loss States

However, renters are not solely responsible for the gap in residential insurance coverage observed between high- and low-loss states. Although most financial institutions require home insurance as part of a mortgage agreement, insurance can sometimes lapse or insurers can cancel policies. In addition, those who have paid off their homes are no longer required to purchase insurance.

Thus, homeowners insurance coverage was relatively common in both high- and low-loss states. However, contrary to what we would anticipate based on the likelihood of loss, homeowners in high-loss states less frequently reported coverage than homeowners in low-loss states (91% vs. 93%). While this difference is small, it represents about 8.8 million Americans living in uninsured homes in 11 high-loss states, which is about 240,000 more than the number of Americans residing in uninsured homes across all 39 low-loss states.29 This difference may also grow in the future as insurance providers reconsider offering new applications for coverage in high-loss states.

Figure 4. Homeowners in high-loss states less frequently carry homeowners insurance.

Percentage with homeowners insurance coverage among homeowners by residence in high-loss and low-loss states.

Note: * Statistically significant vs. homeowners living in low-loss states (p < 0.05). N = 3,991 respondents. These analyses focus on homeowners who knew if they held home insurance.

Lower-Income Homeowners Are Less Frequently Covered by Insurance

Along with fewer insurance options and different perceptions of risks, the ability to afford insurance plans is one barrier that prevents insurance takeup. Cost may play a role in the homeowners insurance gap observed between high- and low-loss states. In states prone to natural disasters, insurance premiums can be more expensive, but residents in these states also typically have lower household incomes.30, 31 To understand whether affordability is associated with the lower takeup of residential insurance in high-loss areas, we show how homeowners insurance coverage varies by household income in high- and low-loss states.

First, consistent with prior findings, homeowners with lower incomes less frequently carry insurance.32 We find that this is true in both high- and low-loss states. For instance, regardless of disaster loss, about 3 in 4 homeowners with household incomes less than $30,000 carried insurance, whereas coverage was nearly universal among those with incomes of $100,000 or greater. This suggests that low household incomes may act as a barrier to insurance takeup, regardless of the risk of natural disaster loss.

Second, once income is accounted for, we show that the takeup of homeowners insurance coverage is very similar for homeowners in high- and low-loss states (Figure 5). The one exception to this pattern was homeowners with household incomes between $30,000 and $59,999. For homeowners in this income bracket, insurance coverage was less common in high-loss states than low-loss states (87% vs. 94%). For all other income groups, there was no discernible difference in the takeup of homeowners insurance.

Figure 5. Households with higher incomes more frequently have insurance.

Percentage of homeowners with homeowners insurance by income and residence in high-loss versus low-loss states.

Note: * Statistically significant vs. homeowners living in low-loss states (p < 0.05). N = 3,991 respondents.

Because many high-loss states also have a greater share of households with lower incomes, some of the gap in insurance ownership between households in high- and low-loss states can be explained by differences in the income distributions of these states, where high-loss states have greater proportions of households with lower incomes.33 However, given the greater risk associated with living in high-loss states, we would anticipate insurance ownership in these states to be higher on average when compared with low-loss states, rather than equal. This lack of difference could stem from either an inability to obtain insurance or a difference in consumer preferences.

Helping Americans Prepare Financially for Natural Disasters

Natural disasters can cause considerable damage to homes and belongings, with potential ramifications for financial health. The threat and severity of these disasters will continue to increase, meaning that the consequences to financial health will also likely grow and impact more Americans over time. Understanding who is at risk, what protection they have in the face of a disaster, and if there are barriers to accessing that protection are all critical to helping Americans prepare for the unpredictable.

This brief focuses on residential insurance for renters and homeowners, which can protect against natural disasters. Certain natural disaster-specific insurance, such as flood or earthquake insurance, must be purchased separately, making the insurance market even more expensive and complicated to navigate. Although homeowners and renters insurance cannot cover damages incurred from all types of natural disasters, they offer a baseline level of protection that not all Americans are accessing.

Given their greater exposure to losses, we would expect that residents of high-loss states would more frequently purchase insurance than residents of low-loss states. Instead, we find the opposite. Consumers in high-loss states could be facing barriers to insurance ownership. For instance, consumers in high-loss states may struggle to find any insurance options or they may hold different perceptions of risk. Alternatively, they may struggle to find affordable insurance products. Indeed, our findings suggest that purchasing homeowners or renters insurance may not be financially feasible for Americans with lower levels of income, possibly preventing greater uptake of insurance.

How Insurance Providers, Financial Service Providers, and State and Local Governments Can Help

Insurance and financial service providers, as well as state and local governments, are uniquely positioned to encourage the takeup of insurance by homeowners and renters, particularly in high-loss states. Below, we share several recommendations for these groups.

Help consumers, especially those with low incomes, access affordable insurance options.

-

- Insurance providers can offer subsidized or discounted premiums specifically designed for low-income households. They could also provide flexible payment options, making it more manageable for individuals to afford coverage.

- States could mandate grace periods for consumers who experience financial hardship and struggle to pay their insurance premium on time. Doing so may help individuals keep insurance coverage if they experience cash flow challenges.

- Landlords may also increase the uptake of rental insurance by including it as an opt-out expense that factors into the rent.

Provide consumers with up-to-date information on their risk exposure.

As natural disasters become more severe and affect more people, providing information such as the FEMA data used in this report or the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit may encourage more consumers to purchase insurance, particularly those in high-loss states.

-

- State and local governments could provide information on their community’s natural disaster risks to keep their constituents informed about the need for insurance.

- Financial service providers could also provide this information as part of an “exit package” to homeowners who pay down their mortgage to reiterate the importance of insurance.

- Landlords could also include this information on natural disaster risk in a lease agreement to inform their tenants of potential risks. This could operate similarly to lead disclosures supplied to renters.34

- Given that homeowners and renters insurance covers only some of the damages that might be incurred in the wake of a natural disaster, insurance providers could improve transparency around whether additional coverage may be beneficial to keep consumers informed and adequately protected in the event of a disaster.35, 36

Mitigate the financial risk associated with natural disasters before or after a disaster strikes.

-

- Insurance providers should continue to incentivize the weatherizing of homes and buildings and share information about such programs with consumers.37 Homeowners can see direct savings in their monthly insurance bills from these sorts of incentive programs. Renters may also benefit if they are spared unexpected costs to replace and repair belongings because they live in a weatherized building that is better able to withstand a climate event.

- There is growing interest in the possibility of anticipatory cash transfers to people living in areas about to experience a natural disaster.38 By sending one-time infusions of cash right before a disaster occurs, these transfers can help manage some of the expenses faced in the immediate aftermath of a natural disaster.

- Similarly, insurance providers may consider utilizing parametric insurance to quickly dispense payouts to those affected by a disaster.39

Areas for Future Exploration

This brief focuses on one specific barrier to insurance takeup, but developing a clear understanding of why residents in high-loss states are not insuring their property at higher rates is a critical area of future exploration. To identify solutions, a closer examination of these barriers may be beneficial:

-

- Higher insurance premiums typically found in high-loss states may also contribute to affordability issues. This, coupled with the higher proportion of lower-income households in these states, may mean that households are simply priced out of the insurance market.

- Recent announcements that larger insurers have or will be pulling out of a number of high-loss risk markets may also mean that the choices and availability of policies in these areas is highly constrained.40, 41, 42

- In addition, the comparable rates of insurance coverage in high- and low-loss states among those with similar incomes suggests that Americans residing in high-loss areas may not be aware of their greater exposure to natural disaster losses, potentially due to less exposure to insurance advertising in these areas.

- Alternatively, high-risk residents may have developed an “immunity” to discussions of the risks associated with such disasters, believing that they are not personally at risk or that insurance won’t help.43

- Finally, given that Asian, Black, and Latinx people less frequently purchase residential insurance, it is critical that any investigation of barriers considers the unique challenges experienced in these communities.

Natural disasters pose significant financial risks to Americans. Although insurance coverage for homeowners and renters offers some financial buffer should a disaster strike, there is more work to do to make insurance more accessible and safeguard financial health for Americans who are especially vulnerable to these disasters.

About Our Methodology

The data used in this analysis comes from the 2021 Financial Health Pulse survey and the FEMA 2021 data. The 2021 Financial Health Pulse survey was fielded to the Understanding America Study panel between April 22, 2021 and May 25, 2021 and had a total sample size of 6,403 respondents (total margin of error +/-1.23%). The overall sample is weighted using U.S. Census benchmarks to be representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian adult population of the United States along gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, and Census region.

We use the Pulse data to identify respondents who reported they were covered by residential insurance policies in 2021. We used data from FEMA to identify states that experience high losses from natural disasters. High losses are defined using the expected annual loss, which measures the expected loss of building value, population, and/or agriculture value each year due to natural hazards.44 We employ descriptive statistics to analyze and summarize our data.

For this analysis, we constructed a final sample of respondents who were homeowners or renters, reported on their insurance status, responded to our indicators and race and income questions, and provided information on the state in which they currently reside. As a result, we omitted 752 respondents with missing data, or 12% of the total sample. This left us with a final analytic sample of 5,648 respondents.

- “NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2023),” National Centers for Environmental Information.

- “Disaster Declarations for States and Counties,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, last updated March 2023.

- “NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2023),” National Centers for Environmental Information.

- “2022 National Preparedness Report,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, December 2022.

- Siddartha Biswas, Mallick Hosain, & David Zink, “California Wildfires, Property Damage, and Mortgage Repayment,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Working Papers, March 2023.

- Julia Gill & Jenny Schuetz, “How to nudge Americans to reduce their housing exposure to climate risks,” The Brookings Institution, July 2023.

- Sarah Parker, Nancy Castillo, Thea Garon, & Rob Levy, ”Eight Ways to Measure Financial Health,” The Center for Financial Services Innovation, May 2016.

- “What is covered by standard homeowners insurance?,” Insurance Information Institute.

- Bradford Cuthrell, “What Is Renters Insurance and What Does It Cover?,” MarketWatch, MarketWatch Guides, last updated July 2023.

- “Do I really need renters insurance coverage?,” State Farm.

- P. Bubeck, W. J. W. Botzen, & J. C. J. H. Aerts, “A Review of Risk Perceptions and Other Factors that Influence Flood Mitigation Behavior,” Society for Risk Analysis, Risk Analysis, August 2012.

- Chenyi Ma, Tony E. Smith, & Amy C. Baker, “How Income Inequality Influenced Personal Decisions on Disaster Preparedness: A Multilevel Analysis of Homeowners Insurance among Hurricane Maria Victims in Puerto Rico,” University of Pennsylvania, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, February 2021.

- Vince E. Showers & Joyce A. Shotick, “The Effects of Household Characteristics on Demand for Insurance: A Tobit Analysis,” American Risk and Insurance Association, The Journal of Risk and Insurance, September 1994.

- Tom Baker & Karen McElrath, “Whose Safety Net? Home Insurance and Inequality,” Journal of the American Bar Foundation, April 1996.

- Christopher Flavelle, Jill Cowan, & Ivan Penn, “Climate Shocks Are Making Parts of America Uninsurable. It Just Got Worse.,” The New York Times, May 2023.

- Michael R. Blood, “California insurance market rattled by withdrawal of major companies,” The Associated Press, June 2023.

- “State Farm General Insurance Company®: California New Business Update,” State Farm, May 2023.

- Daria Uhlig, “Climate Change Is Shaking Up Renters and Homeowners Insurance — Here’s How To Get the Best Deal,” GOBankingRates, June 2023.

- Casey Zuzak, Anne Sheehan, Emily Goodenough, Alice McDougall, Carly Stanton, Patrick McGuire, Matthew Mowrer, Benjamin Roberts, & Jesse Rozelle, “National Risk Index Technical Documentation,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, March 2023.

- Calculated from adding the state populations of those aged 18 and older living in high-loss states as reported in 2021 ACS 5-Year Estimates.

- We categorize survey respondents as Financially Healthy, Coping, or Vulnerable based on their FinHealth Scores®. For more information, see our FinHealth Score Methodology page.

- Antonio Grimaldi, Kia Javanmardian, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, & Kurt Strovink, “Climate change and P&C insurance: The threat and opportunity,” McKinsey & Company, November 2020.

- Junia Howell & James R. Elliott, “Damages Done: The Longitudinal Impacts of Natural Hazards on Wealth Inequality in the United States,” Society for the Study of Social Problems, Social Problems, August 2018.

- Leah A. Dundon & Janey S. Camp, “Climate justice and home-buyout programs: renters as a forgotten population in managed retreat actions,” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, May 2021.

- Kyle G. Horst, “Natural Disasters’ Effects on the Rental Market,” MReport, March 2022.

- “America’s Rental Housing 2022,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2022.

- Drew DeSilver, “As national eviction ban expires, a look at who rents and who owns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, August 2021.

- Ibid.

- Calculated using data from 1-year ACS tables on total population living in owner-occupied dwellings in states with high natural disaster losses relative to the total population living in owner-occupied dwellings in states with lower than average losses from natural disasters.

- Leah Platt Boustan, Maria Lucia Yanguas, Matthew Kahn, & Paul W. Rhode, “Natural Disasters by Location: Rich Leave and Poor Get Poorer,” Scientific American, July 2017.

- Rachel DuRose, “There’s no such thing as a disaster-resistant place anymore,” Vox, July 2023.

- Chenyi Ma, Tony E. Smith, & Amy C. Baker, “How Income Inequality Influenced Personal Decisions on Disaster Preparedness: A Multilevel Analysis of Homeowners Insurance among Hurricane Maria Victims in Puerto Rico,” University of Pennsylvania, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, February 2021.

- Leah Platt Boustan, Maria Lucia Yanguas, Matthew Kahn, & Paul W. Rhode, “Natural Disasters by Location: Rich Leave and Poor Get Poorer,” Scientific American, July 2017.

- “Real Estate Disclosures about Potential Lead Hazards,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, last updated April 2023.

- “Which disasters are covered by homeowners insurance?,” Insurance Information Institute.

- “Insurance Supervision and Regulation of Climate-Related Risks,” Federal Insurance, U.S. Department of the Treasury, June 2023.

- Ibid.

- Somini Sengupta, “A New Kind of Disaster Aid: Pay People Cash, Before Disaster Strikes,” The New York Times, July 2023.

- Rohini Sengupta & Carolyn Kousky, “Parametric Insurance for Disasters,” Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center, Wharton Risk Center Primer, September 2020.

- Even those with residential insurance may not have adequate protection if their claims are denied, they incur damages beyond insurance caps, or if the damages are incurred by a natural disaster that is only covered by disaster-specific insurance policies.

- Maanvi Singh, “‘We can’t escape’: climate crisis is driving up cost of living in the US west,” The Guardian, July 2023.

- J.R. Whalen, “More Americans Are Losing Their Home Insurance,” Wall Street Journal, July 2023.

- Lisa Groshong, Tyler Gerson, Jeffrey Czajkowski, Juan Zhang, Laura Kane, & Jennifer Gardner, “Extreme Weather and Property Insurance: Consumer Views,” National Association of Insurance Commissioners, July 2021.

- Casey Zuzak, Anne Sheehan, Emily Goodenough, Alice McDougall, Carly Stanton, Patrick McGuire, Matthew Mowrer, Benjamin Roberts, & Jesse Rozelle, “National Risk Index Technical Documentation,” Federal Emergency Management Agency, March 2023.

Our Supporters

The Financial Health Pulse is supported by the Citi Foundation, with additional funding from Principal Foundation. Since the inception of the initiative in 2018, the Financial Health Network has collaborated with USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR) to field the study to its online panel, the Understanding America Study. Study participants who agree to share their transactional and account data use Plaid’s data connectivity services to authorize their data for analysis.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this piece are those of the Financial Health Network and do not necessarily represent those of our funders or partners.