3 Ways To Measure the FinHealth Effects of Emergency Savings

This research was produced by the Financial Health Network in collaboration with BlackRock’s Emergency Savings Initiative (ESI). ESI is a cross-sector program with a mission to help people living on low to moderate incomes gain access to and increase usage of proven savings strategies and tools – ultimately helping them establish an important safety net.

By Financial Health Network

-

Program:

-

Category:

Key Findings

As organizations work to measure the impact of emergency savings programs, they should examine a host of metrics and measures beyond balances:

-

- People who save for emergencies are less likely to experience housing or food insecurity after a major medical expense.

- Emergency savings can improve financial health in different ways for different groups.

Measuring the ROI of Emergency Savings Solutions

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, companies, financial institutions, and policymakers have recognized the importance of helping customers and employees build emergency savings. These solutions help people build a buffer of money during good times, so that they can dip into savings during hard times, rather than take on costly debt or experience hardship.

As a growing number of organizations invest in emergency savings solutions, many are searching for the right ways to evaluate their return on this investment. With traditional savings instruments, institutions have measured success based on continuing contributions and growing balances. With emergency savings solutions, however, dynamic balances, ease of access, and trends of accumulation and spending are part of the design.

Companies seeking to measure the impact of new emergency savings solutions, therefore, will need to assess new and different metrics. This brief offers three lenses for viewing the positive impact of savings holistically for individuals.

1. Financial Benefit Lens: Access to Savings Reduces the Financial Costs of Weathering an Emergency

Emergency savings enable people to avoid costly credit and hardship, but savings balances alone don’t indicate success. In fact, during an emergency, individuals who can access savings to avoid taking on expensive credit or experiencing hardship typically have declining balances, making this an indicator of successful emergency saving.

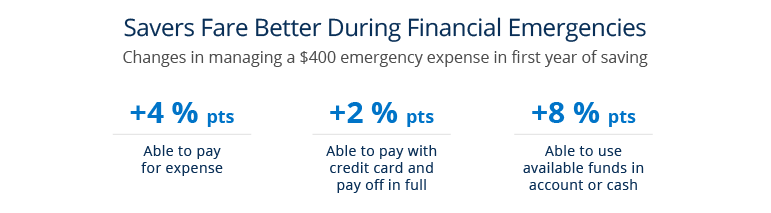

Having analyzed three years of longitudinal Financial Health Pulse™ data, we find that when people start saving for emergencies, they see benefits within 12 months – both in how they think about planning for emergencies and how they manage their finances.

Notes: Results are percentage-point changes in the likelihood of different ways people would pay for a $400 emergency expense, as observed in their responses to this survey question, adapted from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking: “Suppose now that you have an emergency expense that costs $400. Based on your current financial situation, how would you pay for this expense? If you would use more than one method, please select all that apply.” We used a fixed effects model including household income as a time-variant control factor.

Starting to save for emergencies also makes people slightly less likely to access costly credit and financial services – with a small but significant reduction in the likelihood of accessing payday loans, refund anticipation loans, or pawn shop loans. This effect is doubled for women, suggesting that helping women build emergency savings may be an important strategy for reducing financial health disparities by gender.

Financial Benefit Lens: Next Steps for Organizations

Financial institutions and organizations could use credit reporting or fee occurrence to observe correlations between emergency savings and the short- and long-term financial health benefits for customers. If customers using emergency savings solutions are seeing an improvement in credit scores or a decline in fee occurrence, this may signal that the added buffer is allowing them to avoid additional costs or derogatory marks.

For employers, looking at changes in wage garnishment may help. If employees using emergency savings solutions see reduced wage garnishments, this may indicate that they are avoiding using high-cost credit products, such as payday loans. Organizations without access to data at this level of detail or without a large share of a customer’s wallet may be able to capture the impact through surveys.

2. Overall Well-Being Lens: Emergency Savings Can Reduce the Likelihood of Financial Hardship After an Unexpected Expense

A second lens through which to view the success of emergency savings programs is outcomes following an emergency. Savings improve financial health and resilience through a crisis, which in turn allows people to avoid financial hardship. We find that starting to save for an emergency in the prior 12 months is correlated with a 6 percentage-point lower likelihood (23% vs. 29%) of experiencing hardship (e.g., food or housing insecurity) in the prior 12 months.

We also analyzed the likelihood of experiencing hardship while facing a major medical expense. Among people who faced major medical expenses, those without emergency savings were 12 percentage points more likely (36% vs. 24%) to face hardship in the prior 12 months than those who had started to save for emergencies. The biggest difference was in the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity – worrying about how to get more food before one’s next paycheck. This likelihood is 17 percentage points lower (25% vs. 42%) when people have started saving for emergencies in the prior 12 months than when they have not saved for emergencies while facing a major medical expense.

Notes: Different types of hardship were observed through four different survey questions: 1) “In the past 12 months, I worried whether our food would run out before I got money to buy more.” 2) “In the past 12 months, we had trouble paying our rent or mortgage.” 3) “In the past 12 months, I or someone in my household did not get healthcare we needed because we couldn’t afford it.” 4) “In the past 12 months, I or someone in my household stopped taking a medication or took less than directed due to the costs.” If a response to any of these questions was “often,” “sometimes,” or “rarely,” that person was considered to have experienced a hardship. Major medical expenses were observed through this question: “In the past 12 months, have you or anyone in your household experienced any of the following life events? [Option: Major medical expense].” We used a fixed effects model including household income as a time-variant control factor and interacting saving for emergencies with experiencing a major medical expense.

In this analysis, we focus on identifying correlatory links, but dedicated work could improve our understanding of the causal relationships between savings and hardship. For example, using surveys to analyze either experiences or hypothetical situations could provide evidence of the trade-offs people make with and without emergency savings and their resulting effects on hardship. Alternatively, using transactional data to examine spending changes during an emergency – such as a decline in spending on food or changing regularity of rent or mortgage payments – could serve as proxies for experiences of hardship.

3. Equity Lens: Different Populations Feel the Impact of Savings in Different Ways

A final and vitally important lens through which to measure the success of savings solutions is equity. Aggregated metrics are valuable, but splitting them by important socioeconomic factors, such as income, race and ethnicity, and gender, allows us to explore where the benefits of emergency savings are strongest. Our early analysis finds that emergency savings can improve financial health in different ways for different groups.

Looking at the same Financial Health Pulse™ dataset over three years, for example, we saw that while emergency savings improve financial health generally, results differ based on gender. For women, starting to save for emergencies correlates with a 9 percentage-point increase in the likelihood of paying all bills on time, compared with a 5 percentage-point increase for men.

Further, new savings behaviors correlated with different improvements in financial health across races and ethnicities. Among Latinx participants and Asian American participants who start saving, there is a significant increase in the proportion of people with prime credit scores. Among Black participants, the most notable effect of starting to save is reduced experience of financial hardship. These differences are partially rooted in decades of systemic discrimination, which have reduced the ability of people of color, particularly Black Americans, to build and maintain financial health over generations. To address the wider question of equity in financial services and financial health, it’s vital to understand where emergency savings can level these disparities the most.

Equity Lens: Next Steps for Organizations

Understanding why these differences exist and building emergency savings interventions that support more equitable outcomes are important steps for companies looking to improve the financial health of their customers or begin offering emergency savings solutions. Disaggregating survey and transactional data by socioeconomic factors – and diving into contextualizing qualitative and quantitative research – is one important responsibility for organizations looking to tell nuanced impact stories. Although organizational limitations in accessing data, such as race and ethnicity of customers, can pose a challenge, working with the data available to illuminate inequities is a strong starting point.

Assessing More Than Savings Balance Increases

Quantifying and measuring the impact of emergency savings solutions should go beyond simply assessing whether balances are increasing. Three lenses – financial benefit, overall well-being, and equity – offer a starting point for organizations shaping how they expect their emergency savings offerings to support future savers. Using these lenses, organizations can begin to plan their data collection, draft metrics for success, and conduct continual tests to provide a far richer understanding of their effectiveness.

BlackRock’s Emergency Savings Initiative, in partnership with the Aspen Institute, has a working group of research, advocacy, and industry experts who are creating a list of metrics that organizations can use to begin the exploratory process. These metrics, which offer alternatives depending on time horizon, data availability, and priority effects, can further improve our understanding of the impact of emergency savings for customers, employees, and communities. The working group will share the metrics in future publications.

Methodology Notes

In this brief, we analyze longitudinal data from 3,829 Understanding America Study (UAS) panelists who participated in three waves of the Financial Health Pulse™ survey between 2019 and 2021. We weighted this sample to make it representative of 2021 U.S. adult population characteristics with respect to gender, race/ethnicity, education, age, and census regions in 2021. Using fixed effects regressions, we identified year-over-year changes in people’s financial health behavior and outcomes while holding constant factors that stay constant over time for a large majority of people. As with any observational research, the results we present in this brief should not be taken as causal inference, but rather interpreted as correlations within each individual. For instance, a typical interpretation of our results can be framed as follows: “After controlling for changes in household income, people were 6 percentage points less likely to experience some form of hardship when they were saving for emergencies than when they were not.”

Our Supporter

In 2019, BlackRock announced a multi-year, $50 million philanthropic commitment to help millions of people living on low- to- moderate incomes gain access to and increase usage of proven savings strategies and tools – ultimately helping them establish an important safety net. The Emergency Savings Initiative (ESI) is a key part of The BlackRock Foundation’s mission to help people beyond the firm’s core business to build financial security. The size and scale of the savings problem requires the knowledge and expertise of established industry experts that are recognized leaders in savings research and interventions at the individual and corporate levels. Led by its Social Impact team, BlackRock is partnering with innovative industry experts Common Cents Lab, Commonwealth, and the Financial Health Network to give ESI a comprehensive and multilayered approach to addressing the savings crisis.

![]()