Pulse Points Spring 2023: Bracing for the End of Student Loan Forbearance

New analysis suggests that many borrowers anticipate difficulty restarting payments when forbearance likely ends this summer – but proposed policy changes could help.

-

Program:

-

Category:

Introduction

Student loan borrowers have experienced a whirlwind of policy changes since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. To briefly recap:

-

March 2020

The CARES Act placed the vast majority of federal student loans into forbearance, meaning payments were paused and interest did not accrue.1

-

August 2022

The Biden administration announced plans to forgive up to $20,000 in federal student debt for those who received Pell Grants and up to $10,000 for those who did not, with eligibility dependent on certain income thresholds.2

-

Fall 2022

Some states filed lawsuits against forgiveness, obtaining injunctions that halted implementation and culminating in a case that is currently pending before the Supreme Court.3

-

November 2022

Administrative forbearance was extended for the ninth time, until either 60 days after the Supreme Court decision on forgiveness or August 29, 2023, whichever date arrives sooner.4 After this date, payments will resume and interest will accrue.

-

January 2023

The administration proposed changes to income-driven repayment (IDR) plans. Currently, IDR plans adjust a borrower’s monthly payment in accordance with their income for a 20- to 25-year repayment period, with the remaining balance forgiven after the end of the repayment period. The new proposal, which is separate from the proposal being challenged before the Court, would reduce monthly payment amounts on IDR plans even further and shorten repayment periods.5

Many expect the Supreme Court to rule against student loan forgiveness this June and forbearance is unlikely to extend past August 2023, meaning that payments will resume and interest will begin to accrue again.6, 7 Meanwhile, the fate of proposed changes to income-driven repayment (IDR) remains uncertain. With these changes on the horizon, borrowers may face a number of financial challenges once repayment begins.

Default and delinquency on student loan payments are major risks, but resumed payments may cause additional strain with potential ripple effects on other parts of a borrower’s budget.8, 9 Prior to the pause, student loan borrowers were more likely to report financial stress than those without student debt and to report spending more than they earn.10, 11 Rather than focusing exclusively on default or delinquency as a potential consequence of the end of forbearance, we look to 2022 Financial Health Pulse® data to better understand who may have difficulty repaying federal student loans when forbearance likely ends later this year and investigate how IDR plans could help mitigate that difficulty.

Over Half of Student Loan Borrowers Have Repayment Concerns

In the our most recent Financial Health Pulse survey, which was fielded between April 13 and May 15, 2022 (during forbearance but before forgiveness or IDR changes were announced), we asked federal student loan borrowers to tell us how much difficulty they would have making their monthly student loan payments in a hypothetical scenario where the payment pause ended “next month.” Respondents were asked to rate the level of difficulty on a 4-point scale, from “very easy” to “very difficult.”

Over half (59%) told us they thought restarting payments would be at least somewhat difficult, including 29% who said repayment would be very difficult. In early 2022, 43 million Americans had federal student loans subject to forbearance, meaning around 12.5 million borrowers would find it very difficult to make monthly payments.12

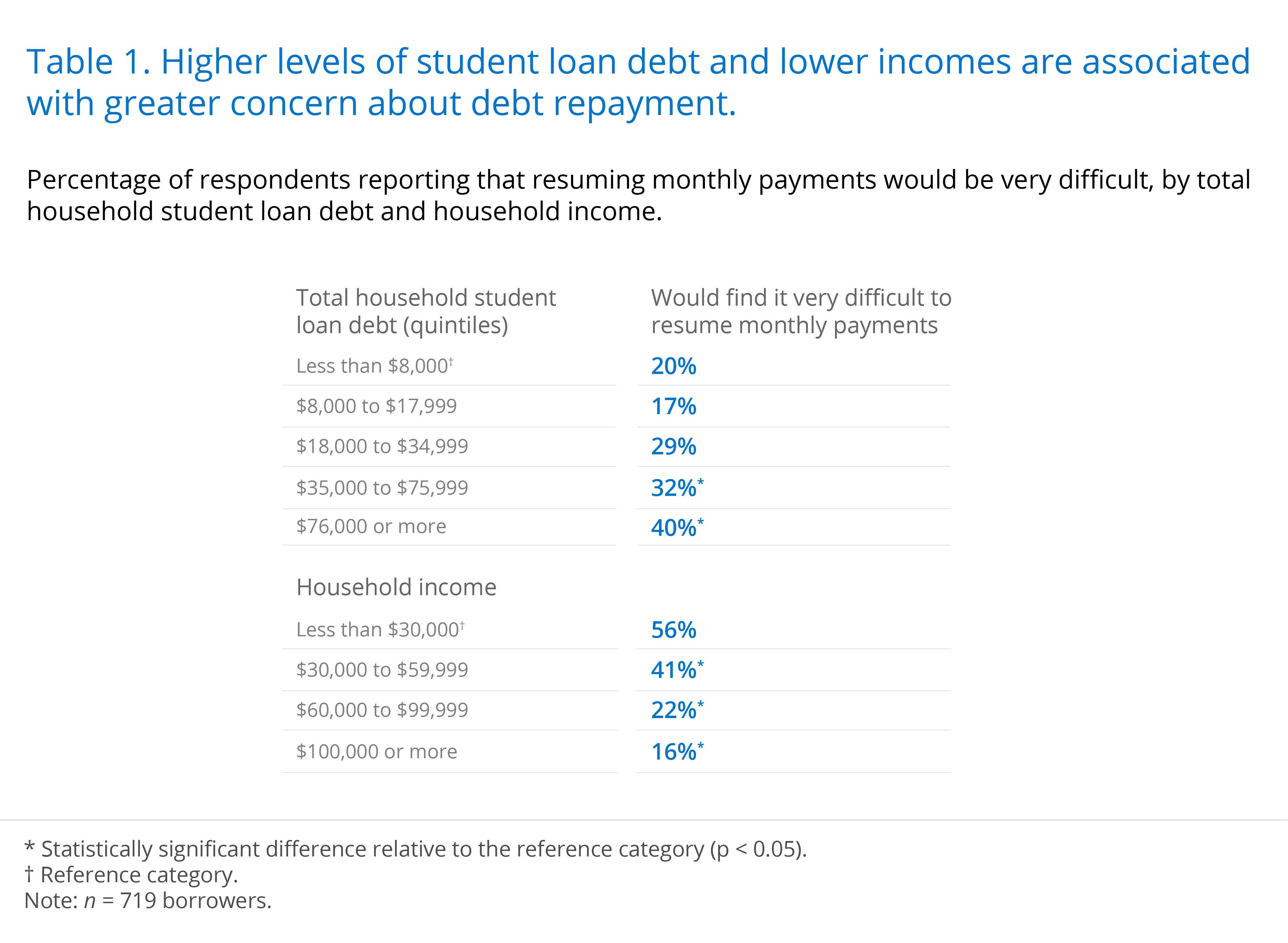

Borrowers with higher student loan debt balances and lower household incomes more frequently anticipated finding repayment very difficult. Those with total loan debt between $35,000 and $75,999 or greater than $76,000 more often anticipated difficulties with repayment. In addition, around half of borrowers with annual household incomes under $30,000 (56%) anticipated that repayment would be very difficult, more than three times as often as people with incomes over $100,000 (16%; see Table 1).

Additional Findings

We do not find meaningful differences when examining gender, age, educational attainment, or racial and ethnic identity. However, Financially Vulnerable borrowers anticipated repayment difficulty at a much higher rate than Financially Healthy borrowers (72% vs. 4%), indicating that the end of forbearance may widen financial health gaps.13

Borrowers with both private and federal loans anticipated that starting repayment would be somewhat or very difficult at higher rates than those with just federal loans (71% vs. 55%), even after accounting for different levels of student loan debt between these two groups. Those with private loans may have higher monthly payments and may have had to make payments throughout the pandemic, harming their ability to build a savings cushion to the same extent as borrowers who only relied on federal student loans.

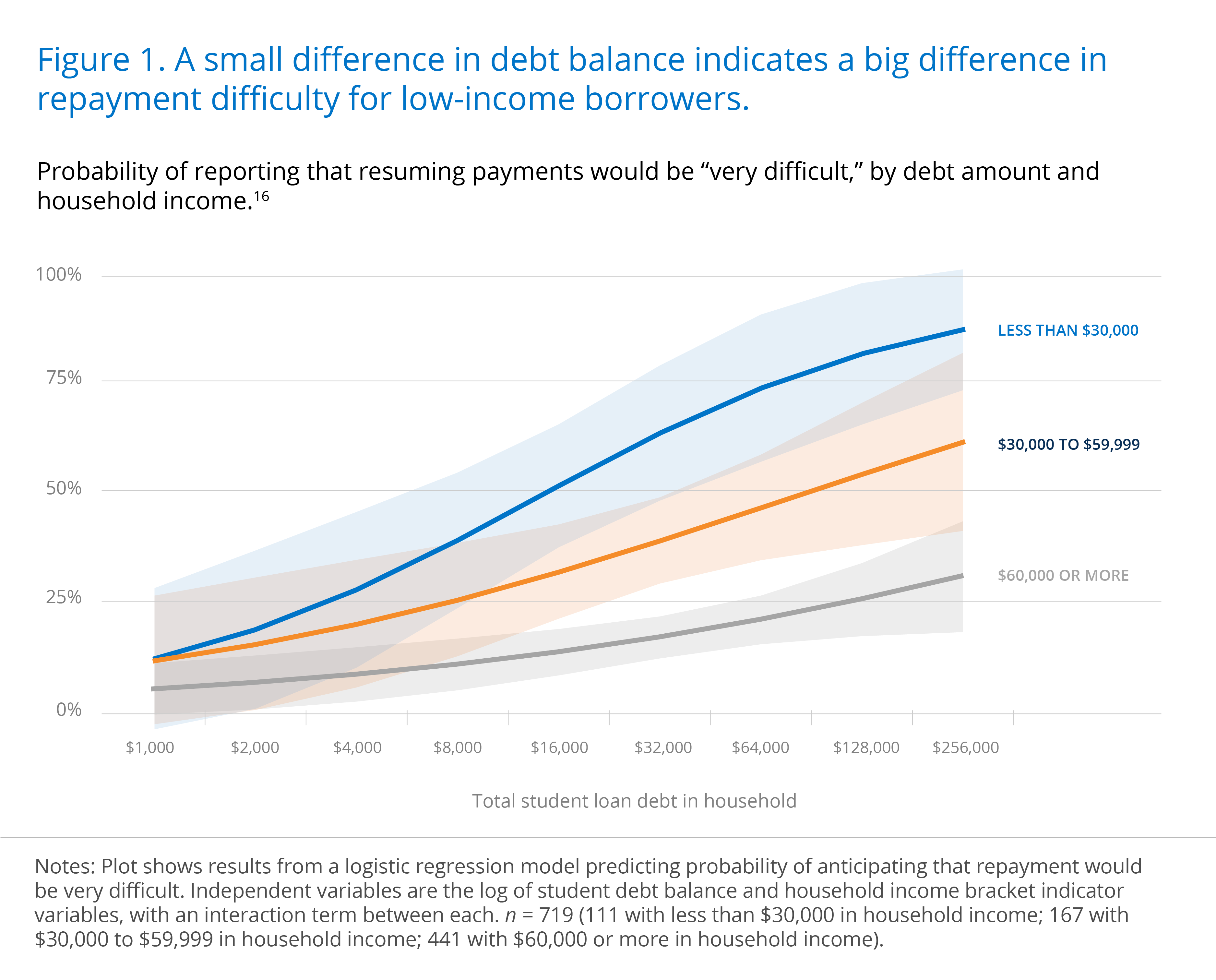

Small Differences in Student Loan Balances Are Associated With Bigger Repayment Concerns for Low-Income Borrowers

Using estimates from a model predicting repayment difficulty based on total student loan balance and annual household income, we find that the relationship between debt balance and difficulty differs for borrowers of different income levels. Starting at about $4,000 in student loan debt, those with incomes less than $60,000 begin to report higher levels of difficulty than borrowers with higher incomes. The difference between these lower-income groups and those earning $60,000 or more then widens as the amount of debt increases (see Figure 1). Put differently, we find that small differences in student loan debt balances are associated with larger differences in repayment difficulty for people with household incomes under $30,000 relative to those with household incomes above $60,000.14

Income-Driven Student Loan Repayment Plans May Be the Key to Supporting Borrowers’ FinHealth

IDR plans, which are targeted toward borrowers with low incomes and/or high debt balances, may help borrowers who anticipate struggling with repayment.

We cannot identify who is on an IDR plan in our data. However, we can roughly identify borrowers who would have lower monthly payments on an IDR plan by comparing their incomes to their student debt load in accordance with guidance from the Department of Education.15 We identify survey respondents whose debt balances are at least as large as their discretionary incomes (household income minus 1.5 times the federal poverty guideline for their household size) and note that they would likely have lower payments under IDR as currently designed. We also identify those whose discretionary incomes are less than $0 and identify them as borrowers who would owe $0 per month on an IDR plan.

Some of these likely IDR beneficiaries are already on IDR plans, but many are not. Prior estimates using federal student loan data show that about 30% of borrowers were on an IDR plan in late 2020.16 Yet, we estimate that around 49% of federal student loan borrowers would have lower monthly payments with an IDR plan, suggesting that approximately one out of every five borrowers (19%) would have lower payments under IDR but are not taking advantage of it.17 Further, we estimate that 16% of federal student loan borrowers in our data would owe $0 per month on an IDR plan.

Borrowers who anticipated struggling with repayment are poised to benefit from IDR at an even higher rate: 7 in 10 struggling borrowers (71%) would likely owe less on an IDR plan than on a standard repayment plan, and over one-fourth of borrowers who anticipated that repayment would be very difficult (27%) would owe $0 per month if they were on an IDR plan. The fact that borrowers who anticipate struggling to repay their student loan bill would owe $0 under IDR suggests that many borrowers who need IDR most are not utilizing it (see Figure 2). Another 44% would still owe some amount per month, but less on an IDR plan than a standard repayment plan.

In addition, the majority of borrowers with household incomes under $30,000 (83%) – a group who anticipated difficulty at much higher rates – would not owe any monthly payments under IDR (analyses not shown). Thus, the high rates of repayment difficulty experienced by the lowest-income borrowers could be meaningfully reduced via increased IDR enrollment, aligning with prior research suggesting that many low-income borrowers would benefit from switching to IDR and that the lowest-income borrowers are actually less likely to be on IDR plans than moderate-income borrowers.18, 19

Under the Biden administration’s proposed changes to IDR, borrowers’ repayment difficulties will likely lessen. If implemented, we estimate that the number of borrowers owing $0 per month under IDR will grow from roughly 16% to 27% as guidelines would shift from defining discretionary incomes as 1.5 times to 2.25 times the federal poverty rate. The new regulations could also improve IDR takeup among the most at-risk borrowers by automatically enrolling those who are 75 days delinquent on payments into an IDR plan.

What This Means for Workplaces, Financial Institutions, and Student Loan Servicers

Analyzing Pulse survey data collected in the spring of 2022, we find that student loan borrowers, especially those with household incomes less than $30,000 or with higher levels of debt, felt unprepared to restart monthly payments at alarmingly high rates. In the year since, it is unlikely that borrowers’ prognosis for repayment has improved, given that delinquencies on other credit products rose for student loan borrowers over the course of 2022.20

Organizations who work with student loan borrowers should prepare for a scenario in which forgiveness is blocked by the Supreme Court and forbearance ends this summer, which could lead to an increase in the share of borrowers who struggle financially, both increasing the number of Americans who are Financially Vulnerable and the hardships of those who already were Vulnerable.

IDR, however, could make the transition back to repayment much smoother; while it won’t help all borrowers, it could meaningfully reduce the high rates of repayment difficulty that many anticipate. Workplaces and financial institutions can play a role by aiding IDR takeup among their employees and customers, as well as providing other forms of repayment support.

-

- Workplaces and financial institutions could promote IDR takeup among employees and customers by sharing information about IDR. Organizations could make sure their lowest-income (and most debt-burdened) clients are aware of the costs and benefits associated with both current and new IDR plans.

- These organizations could facilitate the IDR application process. If a borrower decides that IDR would better prepare them for the end of forbearance, these organizations could help borrowers gather the necessary paperwork, such as documentation of a borrower’s income and family size, to submit an application for IDR.21 Platforms like Summer and Savi work with employers, financial institutions, and individual borrowers to streamline the eligibility and application processes for IDR, loan forgiveness, and refinancing.

- Employers could offer other forms of payment support to borrowers. Over one-fourth of borrowers anticipating serious difficulty would likely not see lower monthly payments under current IDR plans. Employers can directly relieve their repayment burden by incorporating student loan repayment assistance into their benefits packages.

Conclusion

The last few years have dramatically altered the student loan landscape, with paused payments and wide-reaching policy changes in limbo. After three years of paused payments, forbearance will likely end this summer. Many of the borrowers who anticipated difficulty with repayment once forbearance ends would likely benefit from enrolling in IDR. Proposed changes to IDR, if implemented soon, should make payments even easier to manage for an even larger group of borrowers. In the meantime, workplaces and financial service providers can help support borrowers now in identifying and accessing possible solutions to lessen the hit to their financial health later in the year.

About Our Methodology

The data used in this analysis comes from the 2022 Financial Health Pulse survey, which was fielded to the Understanding America Study panel between April 13 and May 15, 2022, and had a total sample size of 6,595 (total margin of error ±1.21%). The overall sample is weighted using U.S. Census benchmarks to be representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian adult population of the United States along gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, and Census region. More information about the Understanding America Study can be found here.

In the 2022 survey, 953 respondents indicated that they personally held federal student loans. 737 of these respondents indicated that the federal student loan pause applied to them, and were thus asked about difficulty with repayment once forbearance ends. These 737 borrowers constitute the sample of interest for this analysis. The fact that only 77% of the respondents who told us they had federal loans affirmed that the pause applied to them indicates some confusion among respondents about what types of loans they own or to whom forbearance applies.

Readers familiar with research demonstrating that borrowers of color are more likely to struggle with student loan delinquency may be surprised that we do not find statistically significant differences in anticipated repayment difficulty by race. This could be for a variety of reasons related to differences in question framing between our survey and others. Another possible contributing factor is that our estimated average balances for our Black and Latinx borrowers are similar to estimates from National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) surveys, but that our estimated average for White borrowers is higher than NCES estimates. Perhaps the 2022 Pulse survey reached a population of more-indebted-than-average White student borrowers, diluting estimated differences between White borrowers and borrowers of color.

We asked survey respondents to self-report the total amount of student loan debt in their household and dropped 25 observations where people reported a balance of “$1” or “$5.” The mean balance is roughly $51,000 and the median is roughly $25,000, which comports with statistics reported by the NCES. We used the natural logarithm of debt in our model to estimate how the probability of difficulty changes with percentage changes in debt amount.

- John Waggoner, “AARP Answers: Student Loans and the Coronavirus,” AARP, November 2022.

- “FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Student Loan Relief for Borrowers Who Need It Most,” The White House, August 2022.

- Jessica Gresko, “Supreme Court student loan case: The arguments explained,” AP News, February 2023.

- Eliza Haverstock, “When Do Student Loan Payments Resume?,” NerdWallet, March 2023.

- “Fact Sheet: Transforming Income-Driven Repayment,” U.S. Department of Education, January 2023.

- Adam Liptak, “Supreme Court Appears Skeptical of Biden’s Student Loan Forgiveness Plan,” New York Times, February 2023.

- “New Proposed Regulations Would Transform Income-Driven Repayment by Cutting Undergraduate Loan Payments in Half and Preventing Unpaid Interest Accumulation,” U.S. Department of Education, January 2023.

- Lexi West, Ama Takyi-Laryea, & Ilan Levine, “Student Loan Borrowers With Certain Demographic Characteristics More Likely to Experience Default,” Pew Charitable Trusts, January 2023.

- Rajashri Chakrabarti, Jessica Lu, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “What Might Happen When Student Loan Forbearance Ends?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, April 2022.

- Robin Henager & Melissa J. Wilmarth, “The Relationship Between Student Loan Debt and Financial Wellness,” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, June 2018.

- Elizabeth C. Martin & Rachel E. Dwyer, “Financial Stress, Race, and Student Debt During the Great Recession,” Social Currents, July 2021.

- “Federal Student Aid Portfolio Summary Q2 2022,” Office of Federal Student Aid, June 2022. 43 million includes borrowers with Direct, FFEL, or Perkins loans, all of which are subject to forbearance.

- We categorize survey respondents as Financially Healthy, Coping, or Vulnerable based on their FinHealth Scores®. For more information, see our FinHealth Score Methodology page.

- Statistical tests used are pairwise comparisons of average marginal effects, which can be interpreted as tests of whether the slopes of each curve are statistically different from one another. Those with incomes between $30,000 and $60,000 are not statistically different from the other two income groups.

- Borrowers whose debt balances are larger than their discretionary incomes (household income minus 1.5 times the federal poverty guideline for their household size) will generally have lower payments on IDR than a standard repayment plan. Those with discretionary incomes of $0 or less would owe $0 per month on an IDR plan. (See the office of Federal Student Aid’s eligibility criteria for more details). We do not have data on the amount of student loan debt an individual borrower holds; instead, we use total student loan debt for the household, which may lead us to overestimate the share of households who would likely owe more than $0 but less on an IDR plan than on a standard repayment plan.

- “Redesigned Income-Driven Repayment Plans Could Help Struggling Student Loan Borrowers,” Pew Charitable Trusts, February 2022.

- We calculate this 19% figure by subtracting the 30% of borrowers on an IDR plan in late 2020 from the 49% of borrowers for whom an IDR plan would likely result in lower monthly payments.

- Ben Kaufman, “New Data Show Borrowers of Color and Low-Income Borrowers are Missing Out on Key Protections, Raising Significant Fair Lending Concerns,” Student Borrower Protection Center, November 2020.

- Sarah Gunn, Nicholas Haltom, & Urvi Neelakantan, “Should More Student Loan Borrowers Use Income-Driven Repayment Plans?,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, June 2021.

- Thomas Conkling & Christa Gibbs, “Office of Research blog: Update on student loan borrowers during payment suspension,”Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, November 2022.

- “Income-Driven Repayment Plans | Federal Student Aid,” Office of Federal Student Aid.

Our Supporters

The Financial Health Pulse is supported by the Citi Foundation, with additional funding from Principal® Foundation. Since the inception of the initiative in 2018, the Financial Health Network has collaborated with USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR) to field the study to its online panel, the Understanding America Study. Study participants who agree to share their transactional and account data use Plaid’s data connectivity services to authorize their data for analysis.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this piece are those of the Financial Health Network and do not necessarily represent those of our funders or partners.