Abbey Wemimo | Esusu

Where you come from shouldn’t determine your worth. This is the underlying belief that fuels Abbey Wemimo, CEO of Esusu, in his quest to promote justice-based capitalism. On this episode of EMERGE Everywhere, Abbey joins Jennifer to talk about his family’s immigration from Nigeria to Minnesota, how his experiences have shaped his views of the U.S. financial system, and his work to bridge the racial wealth gap.

-

Program:

-

Category:

Guests

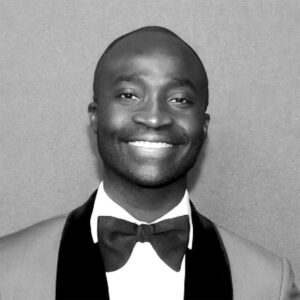

Abbey Wemimo

Abbey Wemimo is the Co-Founder and Co-CEO of Esusu, a financial technology company helping individuals save money and build credit by using rental payment data to boost credit scores.

Prior to Esusu, Abbey founded Clean Water for Everyone, a global social venture providing affordable access to clean water for more than 250,000 people in six countries. He also founded a data analytics company designed to gather machine-readable data on nongovernmental organizations operating in Africa. Previously, Abbey was a Mergers and Acquisitions Consultant at PWC, where he worked on more than 20 deals valued at over $50 billion. He also gained valuable experience working with Accenture, the European Commission, and Goldman Sachs.

Learn more about Esusu and and check out additional episodes of EMERGE Everywhere.

Episode Transcript

Jennifer Tescher:

Welcome to Emerge Everywhere, I’m Jennifer Tescher journalist turned financial health champion as founder and CEO of the Financial Health Network. I’ve spent my career connecting forward-thinking leaders to the growing Fin Health movement. Now I’m sharing these conversations with you, discover how these visionaries are challenging the status quo and improving financial health for their customers, employees, and communities.

My guest today, Abbey Wemimo is the co-founder and CEO of Esusu, a FinTech company that uses rental payments to help individuals boost or build their credit score. From wall street to main street, Abbey has been on a journey to expand equity within the financial system, by challenging the notion that where you are from determines your worth. His passion is rooted in the immigrant experience and the challenges he and his mother faced in building a financial identity as credit invisibles. Over time, he’s come to realize that his experience mirrors that of other marginalized communities, and he’s now focused on unlocking access for all.

Abbey, welcome to Emerge Everywhere.

Abbey Wemimo:

Thank you for having me Jennifer, incredibly excited to be here with you.

Jennifer Tescher:

Abbey, we go back a long way. I mean, it’s got to be maybe eight years from the very beginning of your journey with Esusu. And I think today, Esusu is getting a lot of attention for its solution to help people build credit through their rental payments, but that’s not where you started the journey. That’s not what you were doing when I first met you. Tell me a little bit about the evolution of Esusu, where did it start?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah. Thanks a lot, Jennifer. Yes, absolutely, we’ve known each other for quite a long time now. I think we met sequel to my graduate school experience at New York University. So the theology of Esusu really started by my co-founder and I, Samir, trying to get a group of people who save in a collective using the oldest form of banking, which is rotational savings, and some individual savings. And what we found out is that the regular statistics is a lot of people in this country have less than $400 in their bank account, and we wanted to make sure, particularly low to medium income people, have the opportunity to save as a collective because that’d increase their ability to save. What we found out was people were just not getting paid enough to put money aside. And savings is really hard if you don’t have enough cashflow, especially if you’re spending a large chunk of your amount on certain fixed expenses. So Esusu started as a savings business, and then-

Jennifer Tescher:

And I think that’s where the name of the company came from, right?

Abbey Wemimo:

Exactly.

Jennifer Tescher:

Because Esusu is, if I’m not mistaken, it’s a Yoruba word, right?

Abbey Wemimo:

Precisely.

Jennifer Tescher:

For a rotational savings?

Abbey Wemimo:

Precisely, it’s a Yoruba word for rotational savings where folks come together. And it also stands for something bigger because of the collectivist nature, which is if you want to go fast, you go alone. But if you want to go far, you fundamentally go together because our futures are essentially tied together, but that’s the concept of rotational savings in the Yoruba West African culture.

Jennifer Tescher:

Got it, and so after that, now people, it was challenging for them to save. So then what?

Abbey Wemimo:

It’s challenging for them to save, so we went back actually and asked the tens of thousands of people we had on our platform, “Why aren’t you saving as fast? And with the velocity we thought when we created this company?” And the feedback was, “We’re not getting paid enough. What we need is actually leverage.” And something that’s pretty decent that leverages our credit scores. For immigrants, they either lacked a credit score in the American system, or for the 70 million people in this country have what we call a thin file, which means they don’t have enough information on their credit profile.

So that was the challenge posed to us in terms of how can you give us more leverage to get access to cheap debts, which is fundamentally what this country was built on. And then by doing that, we can lend at a better interest rate, not a drag on your interest with like a 400% interest that’s from bad predatory lenders, so that was the inspiration. We took the feedback and created this product, which essentially does rent reports and to help people establish or build their credit scores.

Jennifer Tescher:

Tell our listeners a little bit more about how it works. If I’m an individual renter, can I sign up? Or, is this something that you need to sign up the landlord first before tenants, if you will, can subscribe?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yes, the way it walks is Esusu predominantly works with large property managers and asset managers, so landlords and property managers, to capture the rental data because it’s just more efficient in that way and we can verify the information, transform it’s in accordance with over 4,000 rules and regulation, including the Fair Credit Reporting Act, the Privacy Act, and all the rules and regulation, and then reports it in an acceptable language the crediting agencies accept, and that data is then reflected in the consumer’s credit profile. So that’s essentially how it works, but to your question, we work predominantly with large landlords and their property managers.

Jennifer Tescher:

So here’s what I don’t understand, your company Esusu, we’re really proud to have you as part of our financial solutions lab accelerator, but at the financial health network we have been investing in similar solutions for over a decade. So the credit bureaus have started accepting this kind of data quite some time ago. We invested in one of the very first companies that made that so, and they’ve made a lot of progress with their own systems, but still we don’t see rental reporting as standard and ubiquitous, why is that? Why do we still need folks like you pushing this issue?

Abbey Wemimo:

It’s a good question. I think we need to go back a little down memory lane, to understand why this is an issue. I think it’s also woven into our own story, so I think one of the important things I like to share, and my co-founder also, is to just tell you the reason why we started the company in the first place and the steps we’ve taken to make sure we are able to drive the policy decisions from Congress and drive it through execution at scale because that’s really what is here. So from a story standpoint, I think one thing that I’m really passionate about is where I come from, I grew up in the slums of Lagos, Nigeria. I was raised by my mother and supervised the sisters, says one thing my mother fundamentally believed in was the importance of education. She had forwarded my school fees to one of the finest high schools in the land.

And although I had the opportunity to go to class with the president’s kids, or the minister’s kids the destitution of my special position did not necessarily limit my imagination. So when everyone was essentially taking their SATs, I jumped on the bandwagon and took SATs and passed, and got admission to the University of Minnesota. So I immigrated from 80 degree weather in Lagos to -20 degrees in Minnesota. But here is where my experience and my mothers experience sort of clashed, when we assimilated to the American financial system. When we made that leap, particularly myself, I didn’t have a credit score. We walked into one of the largest financial institutions to borrow money, we were turned away and had to go borrow money from a payday loan lender at over 400% interest rate. In addition to that, my mother pawned my father’s wedding ring and a bunch of other jewelry, and that’s how we got started in the United States. So really inspired by that experience.

And my co-founders, we started the company on three core premises, where you come from, the color of your skin, and particularly your financial identity shouldn’t determine where you end up in this country. The reason why that context is important is because it is very, in our opinion, it’s important for you to fuel the issue, right? And that’s what fuels your every day. To your question about, why haven’t we seen a lot of movement in this particular space of capturing rent, reporting it, is our system is set up to essentially capture debt obligation, right? Not run rates obligation.

So your debt’s obligation is you need to go into debt and that data is being reported to either establish or build a credit identity. The golden question, however, is what happens if you don’t actually have the ability to participate in getting the debt in the first place? Precisely what happens to my mother and I, where our only alternative was to go get a payday loan, right? So the system treats you like you’re guilty until proven innocent. You get a credit, and then you have to contribute towards it to essentially prove a point, which doesn’t make any sense. So to that end Congress passed a policy for alternative data, which rents and utilities where bucketed. But what happened was there’s a difference between policy and execution. So, when Congress passed that policy, there were a lot of business to consumer activities going on in the marketplace.

People wanted to capture rental data from individual residents and report it into the credit rating agencies. The credit rating agencies like to deal in an institutional manner because of the complex rules and regulation. So, what we decided to do at Esusu is make it our core focus to capture this data at scale from the property management system of record, transform it and report it in the acceptable format. So, all stakeholders are satisfied. The landlords do not do any work because we serve as their agents. The policy makers and the regulators are happy because we want to follow the letter and the spirits of the law. And then the credit rating agents are happy because we’re furnishing correct information into them. That was the bottleneck in terms of having a platform that can get that done, not just the unique products that deal with individual consumers.

Jennifer Tescher:

I see. And I’ve got to believe one of the biggest challenges is the fragmented nature of the rental housing market. You’ve got some very large property owners and managers, but they still only account for a relatively small percentage of the overall stock. I mean, I think about my experience back in the day at Shore Bank, where we made loans to small people who owned a 16 unit building, or just a six flat here in Chicago, how are you planning to address that?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah, you bring up a very, very big challenge, which is the real estate market – 30 plus trillion dollars – is really fragmented. Multifamily albeit big does not account for the entire universe of housing, particularly rental housing. 109 million people rent in this country, and annual run rates of that rents is roughly 1.6 trillion. It’s a lot of money, but very fragmented. Our approach was very simple. It’s leveraging the Pareto Principle. How can we capture 80% of the market with 20% of the efforts? And the way we do that is connect our technology with the largest property management software platforms. So you think about the Yardi’s, the RealPage, the Entrata and then small landlords also leverage things like AppFolio and other small property management software platforms. And what we spent the last three years doing is what we call building the plumbing, right?

Connecting to all these large property management software platforms and the small ones, so we can have a one to many channel. So if we go to a landlord, you don’t have to do any work. We already have the APIs built in. All you do is to ratify an agreement and we can help you and your residents report this data into the credit rates and agencies. So that tell, the way to essentially address it, especially with the huge shift to technology, is capture the data from how they’re getting paid, right? And then go to the small business. Go to the small landlords and say, “Hey, I’m already integrated. You don’t have to do additional work.” And the data flows seamlessly. So, that’s one of the strategies we’ve leveraged. That’s paying a lot of good dividends for us. Be that as it may, there’s a lot of work to be done on this sort of vertical.

The president came up with a mandate, January of this year, saying rental data should be incorporated. No questions asked in residents’ financial identity. And, the government agencies are coming up with mechanisms. So we’re really, really excited about the regulatory headwinds we’re getting, which would help continue to capture this data at scale. But at this point what we’re focused on is the one to many channel, focusing on the accounting system that can help us capture this data at scale.

Jennifer Tescher:

Got it. That makes sense. So this is an incredibly challenging time, I must imagine, to be working in the rental housing market, because as we all know, there’s not enough of it. And what is there is too expensive. People who can’t afford it. And particularly with the pandemic, lots of people benefited from rent moratoriums, although they were unevenly applied. And now those moratoria are coming to an end. Talk to me a little bit about what you’ve been seeing on the ground, given that you’ve been working so closely with actual renters and their landlords and what Esusu has been doing to be part of the solution?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah. I’m glad you asked that question. We are facing one of the greatest health crises of our time, and then the financial crisis to come with that. Thanks to certain government policies and initiatives, we’ve essentially averted at least for now. So what we have seen on the ground is the majority of households, particularly low to medium income, special emphasis on African-American households, Latino households are struggling to pay rent. You know, the last time we checked on our platform, there were close to 42% of folks that can’t afford to pay their rents on time. This is pronounced because we work with predominantly low of medium income folks. Given the construct of the folks who reports to rental data into the credit rating agencies. Number two, from a financial standpoint, our application have essentially captured close to $119 million in requests for folks that essentially said, “Esusu, can you help us with some kind of rent relief?”

So given this backdrop, last year, prior to the government essentially deploying rent relief initiatives, we started and said, look, we need to have zero interest loans provided to folks that can’t afford to pay rent. Because the bare minimum of what we can do is to keep people in their homes, which serendipitously is Esusu’s mission. And our vision is to leverage data to bridge the ratio of gap. So we felt as though we had a duty to stand with folks. So we wrote out a zero interest loan program that essentially is a 15 months term loan, whereby we capture philanthropic dollars from large institutions that usually form homelessness. And our argument to them is, we should not stop homelessness backwards when people are already on the streets. Let’s use some of that capital to actually keep them in their homes, but it’s a revolving pool of capital when they pay back.

And we’ve been doing that for close to 16 months now. And the program has been incredibly successful. Prior to that program, Esusu’s landlord had coverage of over a quarter million rental units. Now it’s 2 million rental units in 50 states. So by doing good and keeping families in their home, it’s also been accretive to growth, and a performance also.

Jennifer Tescher:

I think during this last 18 months, we’ve seen a lot of relief programs, whether for rent or other kinds of needs really in the form of cash, right? Here’s some money. You intentionally did not design this in that way. You designed it as a loan, albeit interest free. Talk to me a little bit more about the decision to go that route. And also if someone can’t afford to pay their rent, are they really able to even make payments against the interest free loan that you’ve made them to hold them over?

Abbey Wemimo:

That’s a fantastic question. So we decided to go this route by offering what we call a zero interest loan program. And if folks can afford to pay, we’ll work with them on a long term payment plan. The argument from others is if you offer free cash, you’re disincentivizing folks to participate in the economy.

And we looked at that from the on set, we didn’t want that rhetoric. Especially being a venture backed business. We had to come up with something that’s not mutually exclusive, but it’s a win-win solution for everyone involved. The way we constructed our program is simple. We engaged with our landlord partners. The last thing they want is for them to pay us. And we are not a credit to their bottom line. The way we constructed the program was actually strategic. We offer a zero interest known to the residents, and once they go through the process, we pay the landlord directly. So we can verify to those philanthropic partners we promised, we’re going to use that capital to keep people in their homes. If we give them the cash, they can use it to make other obligation, which is great.

But the promise we add to our philanthropic partners and other capital providers was, we’re going to leverage this capital to keep people in their homes. That’s one of the decisions to essentially structure this program this way. Number two, you have to also understand that prior to the pandemic where cost item on the balance on the PNL of our landlord partners. But now there’s actually an accredited value, because instead of going through an eviction process or being cash strapped in a classical residence, now being able to pay their rent. Esusu is not standing there and giving them a zero interest loan.

And if you think about the mechanics of how we do this, it’s a 15 month term loan. Three months is essentially a moratorium and they pay on equal installments for the next 12 months. We’re what doing is giving them that first three months to get back on their feet. Provide them with a lot of resources, social services within their zip code, job train workforce. We refer them to all those resources. It becomes a collective, not just what Esusu is providing.

Furthermore, if they can’t pay, we’re not taking them to collections. We’re working with them and saying, “What kind of payment schedule works for you?” But what we want to do is get people in their habit of making obligations because when we help them establish and build their credit scores, outside of the walls of Esusu. If you have other loan obligations, you need to pay it back.

That’s the habits we wanted to foster. Hence why we constructed the program in this way. I know there’s the argument of just giving them cash and then they’ll do what they need to do with it. But given the construction of the capital we have, we want to verify we kept people in their home. To establish and build their credits and then can help them pave their permanent path to some kind of financial stability.

Jennifer Tescher:

Understood. Maybe this is a pre pandemic question. Although maybe the pandemic doesn’t really matter. Do you find that most of the renters you end up working with, just have poor credit or no credit? Because those are two different things. And I know that Esusu in particular, given your personal history, have a passion around the credit invisible. I’d love to hear a little bit more about how that breaks out in who you’re working with, and whether you see differences in either their behavior, or in the benefit that the rental reporting has on their credit score?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah. Thanks a lot for that question. If we look at the demographic we work with, at this demographic, the system has treated them guilty until proven innocent, in the first place. They have forced engagement to the financial systems, either I paid a loan, or they have high interest debt because they have a poor credit score to start off with.

To answer your question, 70% of the folks we work with have very low credit scores. Below 600. And what we are able to do is report 24 months of historical rental payment, provided they pay on time. To help boost their credit scores. And if they don’t have their credit score for that 30%, we can help them establish it for the first time. That’s the power of what we do. And then as it relates to the financial products, it is one thing to help establish or build someone’s financial identity.

It’s also important to let them know, “Hey. This is what you can do with it.” As relates to this, we’re also thinking about what are the low interest capital providers that we can pair them up with? So they don’t fall in the hands of the Draconian providers of loan capital. We think this is important because if we go down memory lane, this country we reside in, was built on cheap debts. We can talk about the construct of slavery in and of itself. The big debts there. You can talk about reconstruction, the world’s reversal. You can talk about, in the 1930s , Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s new deal, whereby the fragile housing authority did not back the mortgages of African Americans and other people of color. And did with the full faith of the federal government for mostly white households.

Those GI bill, those veterans that came back and other white families during that time, have essentially seen a huge benefit from having big accredit value in their homes. And when we think about the racial wealth gap in our country today, the average white family has 10 times as much wealth than the average black family. 76% of that composition is home ownership. As we think about what we are building at Esusu is, “Look. The system is what it is. How do we help folks establish or build their credit scores, so at least they can get access to financial product as a cheaper rates than the cost of capital is not completely expensive for them.”

That’s the dynamic of what we’re focused on. But doing that in a more automated way, not in a nomothetic approach, not in one size fits all approach. Rather, an idiographic approach whereby what’s seeking into context what’s going on in their life and pairing them up with the right financial products.

Jennifer Tescher:

Got it. You speak about the history of racism in this country, history of slavery in this country, more eloquently and more knowledgeably than many people who were born in this country. And I wonder if you might reflect a little bit on the experiences that you’ve had as an African immigrant to this country, and how those are similar or different to challenges faced by black people in the United States, who were born in this country? And how has that played out for you as an entrepreneur, seeking your own capital to start your own business.

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah. Thanks a lot for that question. The journey is somewhat similar. And I would actually say tough, particularly as you think about the African continent. From where I’m from in Lagos, Nigeria, your father’s last name determines the kind of loan capital you can get, to essentially move forward. My mother had to sacrifice 60% of her salary to afford my school fees to one of the best high schools in the land. To give me an opportunity and have this dialogue today.

Coming to the United States, there’s a lot of historical context and I believe I stand on the shoulders of many people that have sacrificed a lot, African Americans for us to do what we are doing today. But the journey, if you look at it, is almost the same. If I’m walking down the streets in Brooklyn or South Side of Chicago the police are not going to say, “Hey. You sound African or you’re African American.” I’m black. You call a spade a spade. And we’re going to be treated the same way.

Although I have an African background, coming to the United States what really matters, and what joins us together, is our inextricably black experience in this country. Which is one of marginalization. And then if you understand the history, it helps you bring things into context. But what I’m particularly focused on for my entrepreneurial journey, and I’d say Esusu is, how do we move beyond the rhetoric? And how do we bring things to action, to actually have an impact in people’s lives?

And that’s what the construction of the Esusu in and of itself. The journey we are focused on is, “Look. We understand the historical context.” Now, I’m notorious for saying ‘Martin Luther King had a dream.’ Guess what? At is Esusu we have a plan. The plan is simple. Folks have been left behind predominantly. We have a capitalist system, in my opinion, that is a mansion built on sinking sand.

We need to lace it with a little bit of justice. We need to have a renewed sense of capitalism, which we call justice capitalism. One that’s more fair, equal. And just for a lot of people that have been left behind. Partiality African Americans, one way we can do that is…

Yeah, categorically African Americans. One way we can do that is look, we talked about and established the fact that cheap debts essentially built America. Let’s establish and build people’s credit scores. If they can’t afford to put a roof over their head, let’s give them zero interest loans. It’s no different than what we did in the 30’s for white families, right? And once we help them, give them zero interest loans and stabilize them, the next step is, guess what? They have good credit. They have a good roof over their head.

They can get a credit card at a cheaper interest rates, they can live in a good neighborhood when they’re thinking about a mortgage, and now we can think about wealth once they have homes and other assets like insurance. That’s the evolution we’re really focused on at Esusu. But it takes a shift and a mindset from just the current capitalist system whereby the coefficient is unsustainable or one that continues to see everyone as fair, equal and just. So that’s what we are trying to deal with, is strict juxtaposition of the current states, not casting stones at it, but laying the foundation and lacing it with a little bit of this and asking ourselves, how can we make it better?

Jennifer Tescher:

So how did you get to this point? Because certainly you have the experience, the immigrant experience, experience of growing up in the place and in the manner that you did, but you also spent a bunch of time in Wall Street here in America. So in way it feels like you’re coming full circle. But tell me more about how you got from Wall Street to really being a significant proponent for a kinder, gentler capitalism and for justice.

Abbey Wemimo:

Absolutely. So my journey didn’t necessarily start in Wall Street. When I came to the United States and I stayed in Minnesota, my first job was working for President Obama’s reelection campaign in the Western region of Minnesota. Incredibly white, walked to people’s doors and say, Hey, let’s vote for president Obama. And you have folks with Confederate flags outside.

Jennifer Tescher:

How’d that go?

Abbey Wemimo:

Yeah. I learned a lot about myself. I got a lot of no’s, and it helped me during my entrepreneur journey because you know, had 300 no’s during the VC process, but that is not a reflection of me or the idea we’re building. It just needs a little bit of tweaking to make it more perfect and something people can embrace. It made my skin thicker and understand why people do what they do, just because they don’t agree with my perspective, doesn’t make them bad, which is kind of the status of where we are in this country today.

The left is not trying to talk to the right. No one is listening to each other. But we’re one big American family. We’re all the same. We all want to wake up, tuck our kids in at night, make sure they have a better life than we did. That’s what everyone wants at the end of the day. So going back to my journey, I started my career looking at that lens, and then did business in undergrad and then went to graduate school for development finance.

I thought I was going to go look at the United Nations. What I keep hearing was the private sector, quintessential role is sustainable development. So that led me to go work at Goldman Sachs, the mergers and acquisition of PricewaterhouseCoopers, in deals that over $50 billion does and the buy side on the sell side. So I think a good perspective, I’ve seen what governments looked like, I’ve seen what the private sector looked like, no one could tell me that I don’t understand how both sides play. And that knowledge essentially create this perspective.

How do you create a win-win solution for society? How do you create products that adds a lot of good, but can also add function, are my learning standpoint. Because I do not believe they are mutually exclusive. And that’s how the idea of justice capitalism came into place. My justice background, being a campaign staffer, knocking on doors that is justice. Fighting to make sure folks can have a fighting chance everyday.

And then looking at the capitalistic mindset, you can say whatever you want to say about capitalism, but it’s one of the most successful constructs of markets in the world, point blank, period. How do we mesh both of them together to make sure people are getting a fair deal? People are living in a more just world, and feel like they are being included. And that’s really the inspiration here. So the idea of working on Wall Street, which is not a bad thing, but my experience working in public service also is essentially what gave birth to Esusu, my co-founder and I, to make sure everyone has a fighting chance, and owed strictly to our vision to leverage data, to bridge the racial wealth gap.

Jennifer Tescher:

Abbey, I think that’s a great place to leave our conversation. Thank you so much for joining me on Emerge Everywhere.

Abbey Wemimo:

Thanks a lot Jennifer, I really appreciate you having us. Keep up the good work and hopefully we have more justice capitalists like yourself.

Jennifer Tescher:

Onward!

This has been Emerge Everywhere, a financial health network production. If you liked the show, please help spread the financial health message by leaving a review. And if you have ideas for future guests or thoughts on the show, please click on the link in the show notes to connect with us. See you next time.